Henderson is a sport model

Published 8:52 pm Saturday, October 6, 2012

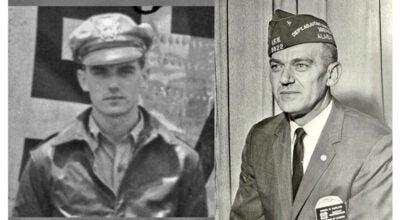

Imagine a 92-year-old so cool that his sons alternately call him by his first name and “Daddy-O.”

Ed Henderson is that cool. I was smitten.

Henderson was the oldest of the four honorees inducted as an AHS Outstanding Graduate this week. As a member of the Class of ’39, he was in the last graduating class at what we now know as Church Street School.

There was a Depression on when he graduated; a great one. The current AHS building was under construction, and was to have a gymnasium. To prepare for that nicety, Henderson and his classmates formed a basketball team beginning in their junior year.

“We picked out the hardest clay part of the football field, and put goals on either end,” he recalled Thursday. “That’s where we practiced. We played every game away.”

School money was tight, and educators made cuts to manage. There was no yearbook his senior year.

But there were excellent teachers.

“Real good teachers,” he said. “They were outstanding in their teaching, their example, discipline, and leadership.”

Henderson was valedictorian of his class and wanted to enroll in college. However, people around here only knew of one scholarship, he said. W.O. Palmer earned only a third grade education, but realized the importance of education.

“He gave a tremendous amount of money for scholarships,” Henderson said. “He set up a foundation, and awarded five in his county (Butler), and one in counties all around South Alabama. Covington had one.”

It was a renewable scholarship, and in 1939, it was in use.

“Ann Albritton was the organist at our church, and we knew about the scholarship because her nephew had it,” Henderson said. “So I had to wait.”

He went to work in a local pants factory, where he toiled for a year-and-a-half, saving money for college. When he mentions the factory, his sons, Bob and Bruce immediately respond. “You’re not going to tell us about sweat on your shoes again, are you?”

Indeed, he is.

“We worked in an old warehouse building,” he said. “It had a metal room and two floors. The production line was on the top floor. When the hot sun hit that tin roof, it was really hot. Within 30 minutes, you’d have perspiration on the tops of your shoes.”

No matter. He was happy to have the job. Decades later, he is still humbled that his co-workers pooled their money and bought him six or eight shirts – seconds from the local factory – when he was going away to college.

“It was the most moving thing,” he said. “Those people didn’t have any money.”

If they kept up with him, they would have been proud.

Andalusia High School had prepared him well for college.

“Auburn was a state school and in those days (state schools) had to take all students from the state. They had to have some way to weed out. Auburn did it with English.”

He also joined ROTC, a move that had a major impact on his future.

“If you went to Auburn, you were in ROTC. Nobody gave it a second thought,” he said.

But before he was done, there was a war on. The ROTC men were taken to Atlanta and inducted, then sent back to Auburn on an accelerated track. The military needed engineers.

Henderson earned a mechanical engineering degree before the war, then returned after the war to complete an industrial engineering degree. His time in the pants factory and his military service in a pipeline unit had prepared him well for that. All students in that field took a survey class. After the first term, armed with practical experience, Henderson taught the class.

Looking back on those days, several things strike him.

“People worked together,” he said. “Really, most Americans were isolationists before the war. They weren’t interested. But Roosevelt saw we needed to be in. We should have been it a long time before we were. Once we were, you did what you had to do.”

The war matured a lot of his classmates, he said.

“People don’t mature at the same time,” he said. “Some always had potential, but didn’t recognize it. Some hadn’t gotten ahold of the handle yet. Some never got ahold of the handle.”

Obviously, he did. He joined Arkla as a management trainee in 1947 and retired as an executive vice president with an impressive resume. He still plays tennis weekly, is active in church and social affairs in Shreveport, and is up on current affairs, which he regularly debates with his sons. When the convertible in which he was riding in Friday’s homecoming parade stalled, he just hopped a ride on a float.

Ed Henderson spent a lot of time this week talking about the people who taught and shaped him. Seventy-three years later, he still has a lot to teach us.

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT