Ever the inventor: Bray’s using drones to save wildlife, help train soldiers

Published 3:34 am Friday, October 20, 2017

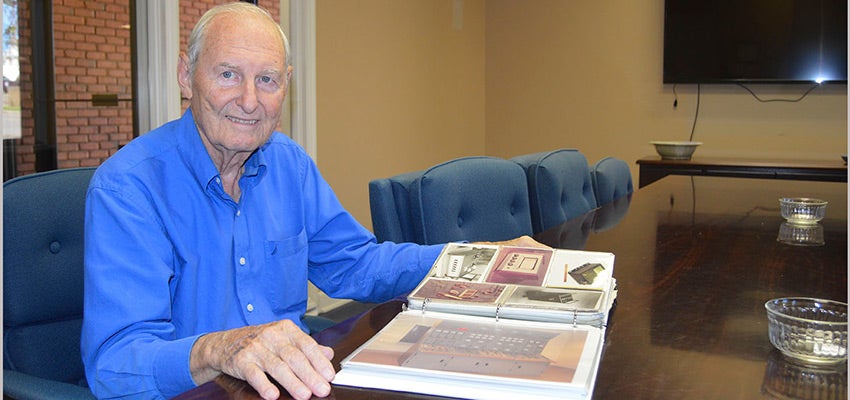

- Bray flips through a scrapbook of products he and his company have developed.

Andalusia High School graduates in town to celebrate homecoming this weekend generally say they are celebrating 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 or even 70 years as graduates.

Class of ’48 graduate Rudy Bray was quick to point out it’s just 69-and-a-half years since he and his classmates crossed the stage and turned their tassels.

And unlike most people celebrating their 69th or 70th reunion, Bray still works at the company he founded, Vertec Inc., and actively developing solutions for the problems he sees in the world, or those people bring to him to solve.

The Pensacola resident holds 13 patents, and his inventions are numerous. His company developed and manufactured a telephone monitoring system for checking implanted cardiac pacemakers; a communication unit for non-verbal patients; air-traffic control training consoles; ATM; all-terrain wheelchairs that allow physically challenged people to easily maneuver on the beach, to name a few. More recently, he’s helped design boats controlled by drones to be blown up by the military in training missions. He also worked to develop an omnidirectional wheelchair controlled with a smart phone that allows handicapped people to be able to dance.

Today, he’s working with a young associate to use drone technology to find poachers in Africa.

“He’s an engineer with the World Wildlife Federation,” Bray said. “There is a huge lake on one of the biggest preserves in Africa. The lake is at the front edge of it, and animals come to get water.

“But poachers come to get animals,” he said. “We are setting up a monitoring system that will monitor activities within several miles of this lake. We’re putting cameras on these towers in enclosures that are mud proof. The cameras can pick up a man’s face in the dark from two and a half miles away.”

The information collected in the control towers will be fed to a control room.

“It’s going to be monitored with some sophisticated programming using artificial intelligence. We’re trying to see who is a fisherman, and who is not.”

The horns of a rhino are worth more than $50,000, he said, and poachers can be dangerous.

He’s also working with drone technology to save black-footed ferrets in the western states, once thought to be extinct.

“This is an interesting little program,” Bray said.

The danger to the ferret is the dwindling food supply, he said.

The black-footed ferrets feed on prairie dogs. The prairie dogs are suffering from disease.

“We got some pills made up to treat the prairie dogs,” he said. “So we will fly out there, drop something that will cure them, and then the black-footed ferrets can eat.”

But Bray said he couldn’t stop there.

“I got to thinking, the prairie dogs get the disease from the fleas on the rats,” he said. “Well. OK. If you’re going to cure the prairie dogs, do something about the fleas.”

They’ve taken the same substance that would be in a flea collar and worked with the Curtis Candy Company to put a candy coating on the substance so it will appeal to rats.

“The next trip, the drone is going to scatter those candy-coated pills to kill the fleas on the prairie dogs, so the black-footed ferrets don’t go extinct.”

Looking back, Bray said he’s always been creative.

“I my garage at home, we always had something going on,” he said. “Some of the guys would come over and see what we were dong. J.C. Howell was a good friend, and he was a creative guy.”

Bray’s father was the superintendent of maintenance of Alatex.

“He would bring things home. Like one time he brought some electric fans home and set them down,” he recalled. “I got to fixing those things and selling them.”

Another time, he brought a small gasoline engine. Bray and his friends worked on it and took it to school to show the class.

“Eventually, we put it on a little wagon. It would run, and you guided it with your feet,” he said.

His father drew the line when young Bray put a propeller on it and attempted to make an air wagon. The elder Bray also squashed a marble-shooting cannon his son built.

As a young man, Bray worked summers at Alatex, and his father made sure he worked with electricians.

“By the time I graduated, I was a pretty good electrician,” he said.

He enrolled in Auburn, but joined the Air Force after two years to avoid being drafted. When he found himself 100 miles behind enemy lines in Korea working with the most advanced radar systems anybody had, he made a decision.

“The Air Force was not for me,” he said.

He went to work for Chemstrand. Eventually, he left the job to return to Auburn and complete an engineering degree.

Asked about the “R” word, Bray said retirement is not really for him.

“My son Ronald is president of the company, so I only work on the projects I want to do,” he said. “And I figure I’ve gotta go somewhere.

“Every time I say ‘This is the last project I’m going to try to fool with,’ something will pop up,” he said. “Just like this business with the Wildlife Federation.”

“Engineering is fun,” he said.

He’s written a paper that he has shared or will share with each of his nine grandchildren at their graduations.

“I tell them it’s not a matter of are you going to make choices, so get used to making good choices. Think about the consequences. “