‘Mystical, mythical beast’

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, December 26, 2018

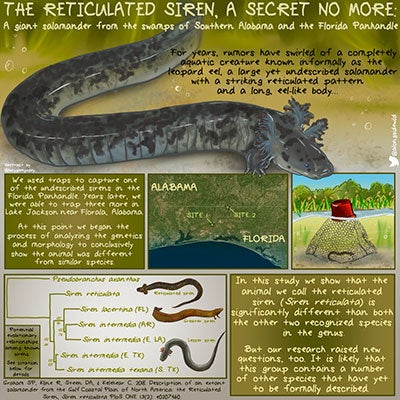

Newly-identified species first found at Lake Jackson

What started as a story said over campfire flames by biologists and ecologists led to the discovery of perhaps the largest amphibian in the world, all tracing back to the quaint Florala.

Or more specifically, Lake Jackson.

This local legend, formerly known as the “Leopard Eel,” is now dubbed the Reticulated Siren.

Sean P. Graham, a vertebrate zoologist from Sul Ross State University in Texas, first heard of the creature on a trip with several colleagues in Georgia.

John Jensen, brought up the salamander to the group, describing it as he’d seen it in the ‘90s.

“John was driving along a small dike separating two marshy ponds near Florala,” Graham wrote in his blog, Living Alongside Wildlife. “Thin sheet flow washed over the road. There was something slithering there.”

Jensen stopped to get out and found dozens of amphiumas and sirens (eel-like salamanders,) wiggling across the pavement.

Jensen described these new sirens as bright yellow-ish green in color with dark purplish green markings, Graham said.

Mark Bailey, a local biologist, said he remembers the day Jensen called and demanded he come down to see the salamanders.

“I was working in Montgomery at the time and I had to work the next day so I couldn’t come,” Bailey said.

“But the next day I managed to get down to Florala and I did see a few of them.”

The salamanders were following their instinct to go upstream.

That night, Bailey took captured video.

“It was 1994, so it was a VHS camera. I don’t know what I did with the footage but I wish I still had it,” he said.

Jensen also told Bailey how a few of them, the day before, appeared to have their heads cut off by a sharp object.

“I’m not sure if locals were scared of the reticulated siren, but it sounded like something or someone cut their heads off,” Bailey said.

Years later, the tales of the Leopard Eel were stuck in the back of Graham’s mind.

When he was a PhD student at Auburn, Graham met Dave Steen, a wildlife ecologist at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center. The two became fast friends.

One day, the story of the Florala Leopard Eel came up in a conversation and Steen couldn’t believe it.

The two decided to travel to Florala in an attempt to find the eel but they had no such luck.

“By September of 2008 we had completed two unfruitful trips to Lake Jackson to find the Leopard Eel,” David Steen said in his blog.

“I was preparing for my Ph.D candidacy exams. These exams include a public seminar of the proposed dissertation research followed by a closed-door meeting with the dissertation committee so that they can test the limits of your knowledge.”

Two weeks before Steen’s exams, his co-advisor contacted him about a recent grant awarded to describe how efforts to restore degraded longleaf pine forests have influenced the ecology of the system.

Steen was told the research was to take place on Eglin Air Force Base.

Steen started research on Eglin in early 2009.

“At dusk, I would visit wetlands to look for watersnakes,” he wrote.

Steen was trying to learn more about the genus of watersnakes; Neordia.

“In theory, multiple and closely-related species shouldn’t co-exist because of high levels of competition where resources were limiting,” Steen said.

Steen would set out crayfish traps for these snakes, hoping to study more about their diet.

Where Steen’s watersnake project seemed to fall through, he started studying more on Loggerhead Musk Turtles instead.

“Checking the traps became a routine,” Steen said.

Until one day, Steen happened upon the Leopard Eel.

“My heart started racing as I lifted up the trap in slow motion to reveal a glistening animal nearly two feet long,” he wrote.

“Largely green but with striking black reticulations, the animal’s external gills pressed against its body and its small legs propelled it around the trap.”

After collecting the Leopard Eel in a bucket, Steen called Graham, only to leave a voicemail.

“I got one. You know what I’m talking about,” he said.

Graham joined Steen in Florida within days.

After seeing the Leopard Eel in all its glory, the next step was to describe it.

Just as they were headed in the right direction to show the salamander to the world, Graham heard of a Florida herpetologist who was also hoping to describe the Leopard Eel.

And he had a 15-year head start.

“We backed down. There are two good reasons why academic scooping is uncommon,” Graham wrote.

“First, especially in herpetology, there is an unspoken expectation of propriety. When somebody has something cooking, we generally don’t butt in out of respect.”

Graham also said it’s risky to edge in on a big discovery.

“If another group has a head start, they can pull the trigger on the discovery at any time.”

“We only wanted to describe the Leopard Eel,” Graham wrote.

The first Leopard Eel was collected in 1970, it was first mentioned in literature in 1975. Jensen found them by the hundreds in 1994.

Graham first heard of the salamander in 2001. In 2009, Steen captured their first Leopard Eel, although it is not an eel.

And in 2018, the salamander has been introduced.

A paper by Steen, Graham and other researchers published earlier this month in the journal PLOS ONE describes the new species and names it the reticulated siren (S. reticulata). According to the paper, the completely aquatic salamander lives in northwest Florida and southern Alabama and has a slimy, eel-like body with irregular spots on its skin, two forelegs, no back legs, and a set of gills just behind its head.

In an interview with The Relevator, Steen described the salamander as “a mystical, mythical beast.