The story of Dr. Sid Phillips PFC USMC WW II Veteran Part 2

Published 6:44 pm Friday, July 17, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Just before leaving Guadalcanal, Sidney Phillips picked up a souvenir. He and his friend, Deacon Tatum, went to the site of a crashed Japanese plane. Quoting Phillips, “I poked around and removed a metal band from some metal tubing. The metal band had Jap writing on it and it was a nice souvenir. I asked Benny [my sergeant] if I could send it to my sister and he said yes. ….I placed it in an envelope, not expecting it to make the trip. Sid’s sister, Katherine was a student at Auburn at the time. She had the metal band mounted on a bracelet. During her trips from Mobile to Auburn, the train was always crowded with few available seats. She usually sat on some duffel bags on the vestibule between the cars until some sailor or soldier came along. Katherine said she would dangle it in front of the first serviceman who came by and tell them that it was from her brother and it was from the first Zero shot down over Guadalcanal. After that, she never had to worry about having a seat again.

Phillips and the Marines arrived in Melbourne in Feb 1943. The local papers announced that these “Yanks” were the troops that had saved Australia. Phillips recalled, “The adults on the streets would look us in the eyes and say, ‘Good on you Yank. You saved Australia’ We southerners gave up on trying to tell them we were not Yanks”. The food in Melbourne was special to the deprived Marines. Phillips remembered, “The Aussies could not believe any humans beings could eat so much. Steak and eggs were the menu favorites…Their beer was very high in alcoholic content and we tried to drink it all, but they never came close to running out”.

One day Phillips became severely nauseated and weak and was taken to a local hospital. He was diagnosed with jaundice [hepatitis A] by the US Army medical personnel running the hospital. The hepatitis ward occupied a whole floor of the hospital. After a week or so, Phillips was returned to his unit. Within a few weeks, he was returned to the hospital, but this time he was a part of the division guard unit, assigned as a security detail. The two weeks were memorable because of the clean, comfortable quarters in the hospital and the great food that was served on real tables with real table cloths. Another special memory came about when Phillips was assigned guard duty at the main gate. “ I was standing at the main entrance….when about six American khaki-colored staff cars pulled up to the curb and out climbed Army generals and Navy admirals in full dress uniform. From the lead car, Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt emerged dressed in an Army WAC uniform…I snapped to attention….Nobody could mistake Eleanor …She walked straight to me and stopped, our eyes were level, I am five ten and she was not wearing heels. She asked ‘Young man, are you a Marine?’ I replied, Yes Mam. she asked, ‘Were you on Guadalcanal?’. Yes Mam, I replied. ‘Are you being well fed?’ I replied, Yes Mam. ‘Are you being well cared for?’ Yes Mam. ‘What state are you from? My reply in a proud tone was, Alabama! Mrs. Roosevelt smiled and said ‘I should have known’

Finally, after nine months, Phillips and battalion left Melbourne aboard liberty ships. The ships had “insufficient bunks and no heads [bathrooms]”. Phillips continued, “Most of us just slept on the open steel deck….We had never been issued mattresses….we had never been allowed to become soft and civilized”. To make matters worse, they were now under Army command. They finally arrived at a large island off the New Guinea coast named Goodenough Island. They trained long and hard on the island. In preparation for their landings at Cape Gloucester, they practiced loading onto LSTs [landing ship tanks] and making practice landings on nearby islands. On one particular landing, complete with Sherman tanks, they moved rapidly inland until they came upon a native village. Phillips recalled, “All the women were only dressed in grass skirts. They all came to smilingly gawk at us and we delightedly gawked back…. Our officers proceeded to get us off that island faster than we had come ashore”. The task force celebrated Christmas Day on the island with a rare turkey dinner. After that, they were loaded aboard a Navy LCI [landing craft infantry] for the overnight trip to Cape Gloucester. Just before leaving New Guinea, Phillips’ battalion received a new commanding officer, Lt.Col. John Masters. He assembled the battalion, gave them a pep talk, and as related by Phillips, “He told us that in the coming campaign, he wanted us to ‘kill the bastards’ whenever we could”. Someone said that Masters had lost a brother on Wake Island. The battalion would now be referred to as “Masters’ bastards”. Phillips recalled, “Col. Masters was the same height as my father and had the exact same colored blue eyes. I liked the man immediately – he hated the Japanese just like the rest of us”.

Phillips’ battalion landed on New Britain, some eight miles east, down the coast from the main division’s landing sight, at the foot of a mountain called Mt. Tuali. The idea was for Phillips’ battalion to prevent the Japanese from retreating up the coast toward Rabaul. He relates that they landed the day after Christmas and their attitude was, “Let’s get on with the program, because the sooner we do, the sooner we can go home and end this miserable war”.

As they landed, the torrential monsoon rains began and continued as long as they were on the island. Phillips remembered, “Due to the gloomy weather, almost everything about the campaign of Cape Gloucester is recorded in my memory bank in black and white”….The Japs hit our lines one dark night during a howling monsoon, lightning and rainstorm. For the Marines, firing their mortars was nearly an impossible task. “Opening the cannisters and getting the correct number of increments on each shell had to be done in the dark by feeling, or in the flashes of the wild lightning….Gunfire and thunder were mixed and confusing. The next morning we had to dig up our mortar base plate because it had settled so deep in the mud. Col. Masters came to our squad the next morning and commended us highly…He asked our names and remembered mine”. At daylight the next morning, the wounded Marines were brought in by stretcher bearers, making their way carefully through the mud and relentless rain. Phillips recalled, “We knew most of the wounded, with some of them from our platoon….It was that morning that I decided I wanted to study medicine, because of the helpless feeling of seeing all the wounded and not having a clue as to how to help them”.

After a few days, it was determined that most of the Japanese had retreated to the north side of Mt. Tuali. Phillips battalion was ordered west to join the main part of the division at Cape Gloucester. After they arrived at the Cape, they were moved around several times, always by foot in a sea of mud. On one of their moves, they came across a Japanese hospital tent. The scene imprinted on Phillips’ mind: “It was a Jap hospital tent about 10 by 20 yards in size, abandoned, with dead Jap soldiers in uniform on canvas stretchers….maybe a total of 20, all reduced to skeletons; no odor but the strange odor like Colgate tooth powder.”

A few days later, the battalion prepared to leave Cape Gloucester. Phillips and a friend were put on an all night working party with some Army troops to help load vehicles aboard ship. First, they had to help unload Army vehicles to make room for the Marines’ gear. Phillips recalled, “We would take a load of Army stuff ashore and come back with a load of Marine gear to go aboard. It was our worn out vehicles going aboard”. They left Cape Gloucester after several months.

Phillips said they were “rumored to be returning to Melbourne and the glorious girls, bountiful beer and fabulous food.” Instead, they were off loaded at an island in the Russell Island group called Pavuvu. It was supposed to be a rest camp. The island was an uninhabited, abandoned coconut plantation, fairly primitive and not far from Guadalcanal. Phillips describes it best, “We had been put into another massive, monstrous mud hole. The native habitat of trillions and trillions of rats and land crabs, equaled in number by the mosquitoes….On Pavuvu, there was no place to go, nothing to buy, no other units like Navy or Army to steal from, no radio, no music, no anything – just nothing to do.” One pleasant thing that happened on Pavuvu was a series of conversations that Sid Phillips had with his regimental commanding officer, Col. Lewis B [Chesty] Puller. Phillips had been assigned KP [kitchen patrol], in this case, the job of cleaning mess kits and the dining area. The KP galley tent [eating area] was set up right near Col. Puller’s tent. Phillips recalled, “I enjoyed hours with him in the afternoons. He wanted to know what state I was from, how many were in my family, if I intended to stay in the Marine Corps etc. When I told him I wanted to go to medical school, I remember he said that wouldn’t be easy, but there was no reason why I couldn’t make it if that was what I really wanted. At that time, the GI Bill had not been brought into existence”.

To be continued.

John Vick

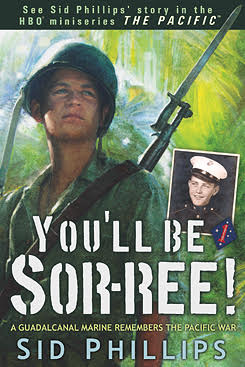

[Sources: Dr. Sidney Phillip’s war memoirs, “You’ll be Sor-Ree”; Parade Magazine, “A fight to the Death” by Hugh Ambrose {2010}; Jistory.net {Steve Santoro}]