The Cuban Missile Crisis – 58 Years Ago this Week

Published 11:45 pm Friday, October 23, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

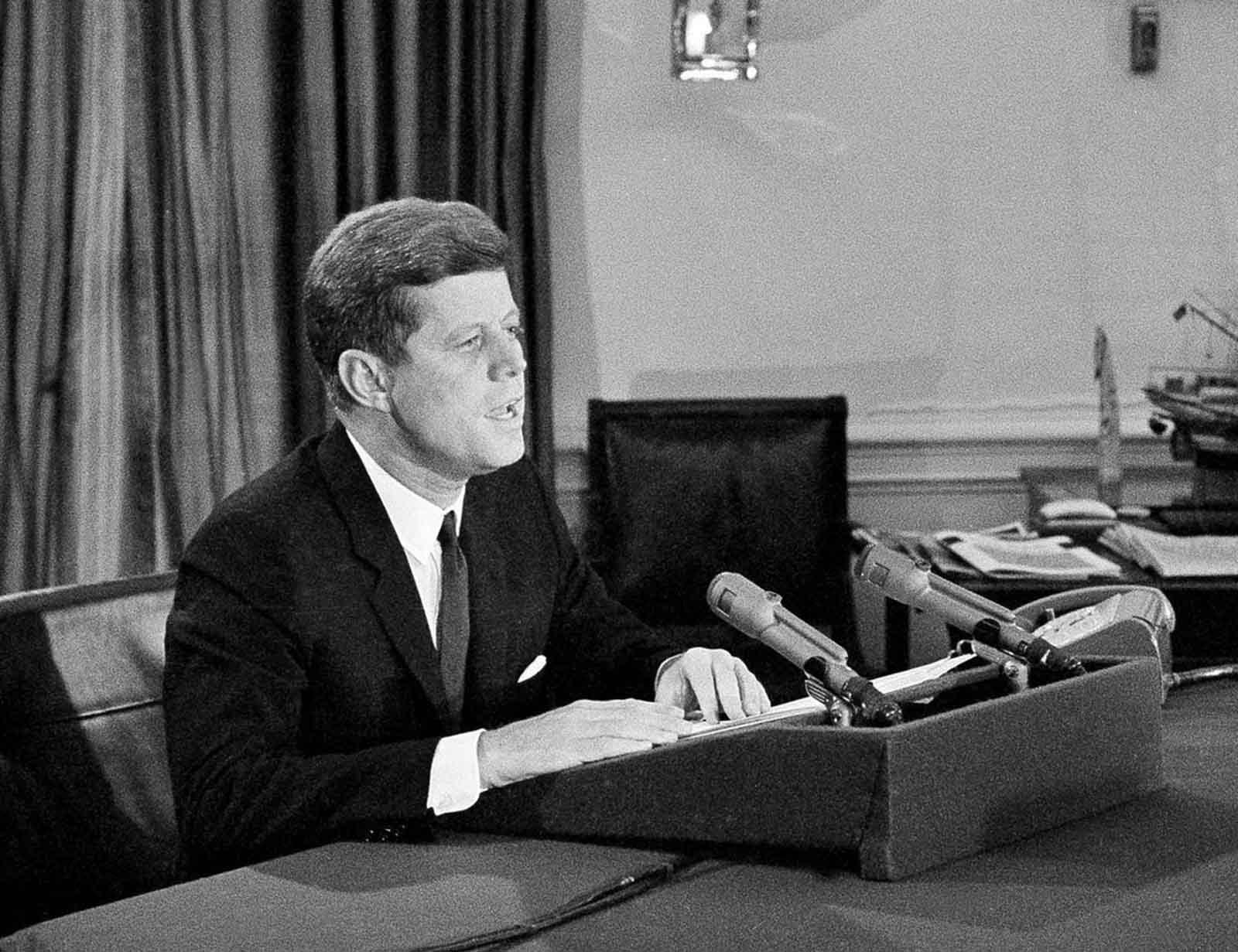

On the night of October 22, 1962, the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy gave a speech on nationwide television. That speech marked the beginning of an international crisis that would grip the world for several weeks. For those of you too young to remember, this article might be a good history lesson.

The speech by President Kennedy set in motion a series of clandestine, diplomatic negotiations that narrowly averted WW III. Those tense weeks of international diplomacy and intrigue came to be known as The Cuban missile crisis. As a young, newly commissioned Naval officer, this author was given a front-row seat to what unfolded that October, 58 years ago.

Sometime, round 1900 hours [7:00 PM, EST] on the night of October 22, I sat with a large group of officers in the wardroom dining area of the aircraft carrier, USS Randolph [CVS-15]. We were quietly cruising the waters of the Atlantic, a few hundred miles due east of Jacksonville, Florida. We were awaiting a nationwide address by the President of the United States. The fleet had been told to expect a very important speech by our Commander-in-Chief.

First, let me set the context for that night. After my graduation from Auburn in August 1962, I had been commissioned an Ensign in the Navy and temporarily assigned to the Randolph. I would be there until my flight training started at Naval Air Station Pensacola, the second week in November.

Randolph was an Essex class, fast attack aircraft carrier during WW II, and had played a vital role in defeating the Japanese. Randolph still carried a reminder from WW II, when she had been attacked by a Japanese kamikaze on March 11, 1945. The plane struck the ship on the starboard side, just below the flight deck, killing 27 men and wounding 105. As a reminder of that attack, one of the large metal propellers from the kamikaze had been mounted on the forward bulkhead of the hanger bay with a memorial plaque that listed the names of the men who had been killed.

The old black and white television in the wardroom that carried the president’s speech was mounted above the deck and was difficult to see. However, the audio portion of the speech was broadcast throughout the ship so that everyone could hear what was said. President Kennedy’s speech was forceful and direct: the United States had overflown Cuba with a U-2 reconnaissance aircraft and had taken clear pictures of Soviet medium range, offensive, nuclear missiles being placed in service. The original flight by the U-2 was on October 14, but it had taken a week for U.S. intelligence to verify the photos and for the President and the National Security Council to plan a response.

The President began by announcing a strict quarantine of all offensive military equipment being shipped to Cuba. All ships bound for Cuba with those type cargoes would be stopped and turned back. The President continued:

“It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.

I call upon Chairman Khrushchev to halt and eliminate this clandestine, reckless and provocative threat to world peace and to stable relations between our two nations….He has an opportunity now to move the world back from the abyss of destruction.”

President Kennedy’s response to Khrushchev’s careless and dangerous actions of placing nuclear missiles 90 miles from the United States began one of the most dangerous confrontations of the Cold War. When it was over, the young American President would gain

international stature for his patient diplomacy in avoiding war.

Back in the wardroom of the Randolph, things were pretty tense. Right after the President’s speech, I noticed a subtle turn of the ship [it turned to 180 degrees, due South] and the increased vibrations from large screws indicated an increase in speed. I thought no more of the ship’s changing directions and speed until the 1MC [the main communications speaker system throughout the ship], blared out an announcement,

“Would the following officers report to the ship’s office immediately: Ensigns Vick, Brown and Smith.” I’m not sure that the other two were named Brown and Smith [after 58 years], but all three of us made it to the ship’s office in short order. The Yeoman in charge explained that since the three of us were due to leave the ship in a couple of weeks, we were being sent ashore immediately because the Randolph was bound for Cuba. He explained it this way, “Gentlemen, be on the flight deck in one hour or you’ll be going to Cuba with the rest of us.”

The orders instructed us to report to the OOD [Officer of the Day] at Jacksonville Naval Air Station, Jacksonville, Florida.

At approximately 2200 hours [10:00 PM], we boarded the COD [carrier onboard delivery] aircraft and were launched into the night sky. As soon as we were airborne, we turned due west and landed at NAS Jacksonville around midnight.

The Randolph would continue south and be the lead ship in the Navy’s massive quarantine operation. The Cuban Missile Crisis would be over in another week or so but not before a confrontation at sea nearly led to nuclear war. That critical moment came to be known as Black Saturday, October 27, 1962. To be continued.

John Vick

[Sources: National Archives; Wikipedia; The Kennedy Library; The Smithsonian Museum; ussrandolphcv15.com]