COLUMN: The Angel of Bastogne-1944

Published 8:41 am Monday, December 28, 2020

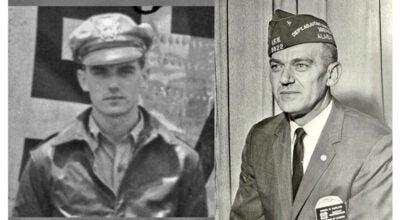

- Army Capt. Jack Prior, MD, Bastogne, 1944 [Photo: morethanmedicine. blogspot]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This column has always been about veterans, mostly local and usually with an Alabama connection. As our country fights through this pandemic, we have come to truly appreciate the dedication and courage of the doctors and nurses fighting on the “front lines.” This week’s column is dedicated to the doctors and nurses fighting on the front lines in a different war, 76 years ago. Their war was a shooting war, with horrific casualties that had to be treated under conditions that are hardly imaginable today.

Around Christmastime, I always recall a conversation I had with my friend Eland Anthony when I was preparing a column describing his experiences in WW II. He talked about the conditions he and his battalion faced when they arrived at the battle front, near Bastogne. They arrived in late December 1944, not too long after the German attack had begun. That European winter was recorded as one of the coldest winters ever, with temperatures hovering near zero most of the time.Anthony recalled, “It was awful, bone-chilling cold when we arrived, just outside Bastogne. I will never forget the sight of dead GIs, stacked up like so much firewood. I thought to myself, ‘This could be us in a few days.’ ”

Anthony was one of more than a half-million U. S. troops that fought in the Battle of the Bulge which lasted from December 1944 through January 1945. Hitler had ordered one, last-ditch attack to try and drive Allied forces back to Antwerp. The attack came at the Ardennes forest, an unlikely choice because of all the trees and deep snow. The attack advanced rapidly against the unsuspecting Allies but had been stymied at the small Belgian town of Bastogne. One of the doctors taking care of the wounded at Bastogne was 27 year-old Army Captain John T. “Jack” Prior, a native of St. Albans, Vermont.

Captain Prior was commanding the medical detachment of the 20th Armored Infantry Division at Bastogne. They were under siege from overwhelming German forces including four Panzer [tank] divisions, two infantry divisions and one parachute division.

Prior’s situation had become more and more desperate as he had lost many of his medical staff on the battlefield. He had set up a makeshift hospital in a three-story private home. He described their working conditions in his diary, “We worked 24 hours a day….the plasma froze and would not run. We had no medical supplies …the town was continually shelled.”

On December 22, the German commander sent a message, under flag of truce to the U.S. commander, Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe. The message offered surrender terms and stated that it required an answer within two hours. The General’s reply was short and direct, “Nuts!” The best German translation was “Go to hell!” and after that, the heavy shelling resumed.

Captain Prior noted that the resumption of shelling was no different than before. With that still going on, he continued to treat the wounded as best he could. “I was holding over 100 patients, of whom about 30 were very seriously injured litter patients. The patients who had head, chest and abdominal wounds could only face certain slow death since there was no chance of surgical procedures – we had no surgical talent among us and there was not so much as a can of ether or a scalpel to be had in the city.” In desperation, Prior turned his litter bearers into bedside nursing personnel.

Captain Prior sent out a message to the public, asking for civilian nurses or healthcare workers who might volunteer. On the morning of December 21, two female nurses showed up. It was only by chance that either nurse was even in Bastogne. Renee Lemaire was a nurse living in Brussels who had come for a Christmas visit with her parents and become trapped by the German attack. Augusta Marie Chiwy [pronounced she-wee]was the daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a mother from the Belgian Congo. She had also been visiting her parents and become trapped.Prior described how they were able to help, “They played different roles among the dying – Renee shrank away from the fresh, gory trauma, while the girl from the Congo was always in the thick of things – splinting, dressing and hemorrhage control. Renee preferred to circulate among the litter patients, sponging, feeding them and distributing the few medications we had [sulfa pills and plasma]. The presence of the two girls was a morale factor of the highest order.”

Chiwy also volunteered to go with Prior and his litter bearers when they drove from Bastogne out into the forest to bring back casualties. With German cannons, mortar fire and heavy machine guns raining down everywhere, they were in constant danger. Once Prior commented to Chiwy that she was lucky that she was so small because that made her a hard target. She replied that “She was just lucky that the Germans were bad shots because her black face stood out in the snow.”

On Christmas Eve, Gen. McAuliffe sent a message to his troops: ”What’s Merry about all this, you ask? We’re fighting – it’s cold – we aren’t home. All true, but what has the proud Eagle Division accomplished….Just this, we have stopped cold everything that has been thrown at us…Allied troops are counterattacking in force. We continue to hold Bastogne. By holding Bastogne, we assure the success of the Allied Armies….We are giving our country and our loved ones at home a worthy Christmas present and being privileged to take part in this gallant feat of arms are truly making for ourselves a Merry Christmas.”

The night of Christmas Eve, Captain Prior and Chiwy finished surgery on a dying soldier and had gone to an adjacent building for a break. They were about to head back when a young Lieutenant stopped them and offered a Christmas Eve toast from a bottle of Champagne. As they raised their glasses, they heard a plane overhead. They both ducked as a huge bomb fell directly upon the make-shift hospital next door. Prior had hit the floor but Chiwy was blown through a wall. Luckily, she only suffered cuts and bruises. They both stepped outside to stare at the massive pile of rubble that had been their hospital. The sky was lit up by the magnesium flares dropped by the German plane, illuminating the snow that was red with blood. Several men helped Prior as they climbed atop the rubble, looking for survivors that were screaming for help. Prior described what happened next, “At this juncture, the German bomber, seeing the action, dropped down to strafe us with his machine guns. We slid under some vehicles and he repeated the maneuver several times before leaving the area….A large number of men soon joined us and we located a cellar window [marked by a white arrow [like most European buildings]. Some men volunteered to be lowered into the smoking cellar on a rope and two or three injured were pulled out before the entire building fell into the cellar.”

Chiwy helped them rescue the wounded. Inside the hospital, all 30 wounded soldiers had been killed. Another 100 soldiers around the aid station were wounded in the blast. Late that night, as they were searching the ruins for more victims, Prior discovered the severed body of Renee Lemaire. She had been killed instantly by the blast.

During the siege, Bastogne was supplied by parachute. All the food, ammunition, blankets and medical supplies were dropped in multi-colored parachutes. Each colored parachute represented a different category of supplies. There was no attempt made to control who recovered the supplies. Even the parachutes were used as bedding in the hospital. Renee Lemaire had wanted to recover a white parachute to use as a wedding dress. On several occasions, Renee had run outside to get a parachute but had always been beaten out by some soldier who had gotten there first. After her death, Captain Prior located a white parachute, wrapped Renee’s body in it and carried her home to her parents. When stories were told of Lemaire’s tireless and heroic work with the wounded soldiers of Bastogne, they called her The Angel of Bastogne.

On the morning of December 26, Lt. Col. Creighton Abrams and elements of the 4th Armored Division, opened a road into Bastogne, lifting the siege. The Battle of the Bulge continued until January 25 when the German army was finally forced back beyond the initial attack point, in full retreat.

Captain Jack Prior returned home after the war and stayed in the Army reserves. When he retired as a Colonel in 1977, he was the Commanding Officer of the 376th Combat Support Reserve Hospital. His civilian work included a position as Professor of Pathology, Upstate Medical Center at Syracuse and Director of Community General Hospital. He had authored more than 80 medical papers. Dr. Jack Prior died in November 2007 at the age of 90. Nurse Augusta Chiwy died in 2015 at the age of 94. Their work with the wounded soldiers of Bastogne became legendary after war.

— John Vick

[Sources: “Searching for Augusta: The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”, PBS documentary by Jasmine Avenue Holdings; myneworleans.com, “The Angel of Bastogne”, Dec. 18, 2012 by Errol Laborde; Syracuse.com, “On Christmas Eve 1944, the Snow Turned Red with Blood”, Dec. 23, 2019 by Michael Ruane; Syracuse.com, “After 70 Years, New Focus on a Legend…”, Dec 21, 2014 by Sean Kirst; Wikipedia]

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT