Max M. Foreman, Seaman First Class, U.S. Navy, PT Boat, WWII

Published 4:30 pm Friday, February 25, 2022

- Seaman First Class Max M. Foreman, U.S. Navy, PT boat, WW II. [Photo: Donlin Foreman]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The author’s phone rang recently on a quiet Saturday afternoon. I recognized the name and number from Houston, Texas. When I answered, the 97-year-old voice on the other end asked, “John, this is Clyde Combs from Houston. How’re you doing?” I answered back, “I’m well, how are YOU doing?” It’s not often I get a call from a 97-year-old asking how I’m doing. Clyde continued, “Have you thought anymore about writing about my friend and ship-mate, Max Foreman?” I replied that I hoped to write something about Max Foreman soon. Clyde Combs and Max Foreman served together on PT 515 during D-Day and afterwards. They were a part of the largest amphibious invasion in history at the time and Clyde Combs kept a detailed diary. So, with Clyde Combs’ help, we’ll try to tell Max Foreman’s story.

Max Maloy Foreman was born April 3, 1922 in Andalusia, Covington County, Alabama. His parents were Emmette Max Foreman and Johnnie Maloy Foreman. Max attended Andalusia schools and graduated from Andalusia High School in 1941. He entered Alabama Polytechnic Institute [now Auburn University] and left to join the Navy in 1943. After basic training, Max was sent to the Motor Torpedo Boats Squadrons Training Center in Melville, Rhode Island. Max and Clyde Combs first met when they were both assigned to PT 515. After commissioning the boat at Bayonne, New Jersey, the crew took the boat to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to take on supplies. Since Clyde was a Quartermaster, he had to bring all of his equipment onboard, as well as navigational charts.

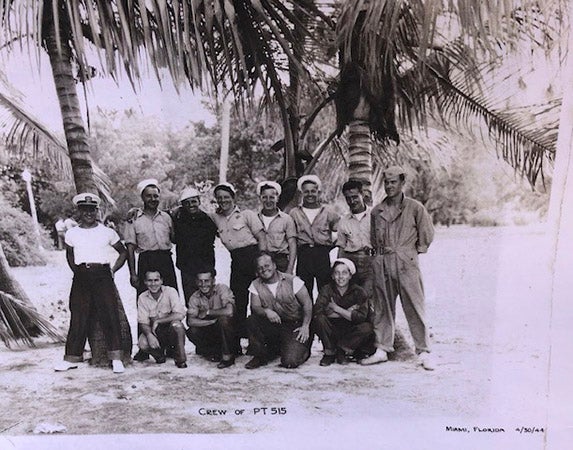

The crew of PT 515 in Miami, Florida, April 30, 1944, just prior deployment to the

European theater and Operation Overlord [the D Day invasion]. Max Foreman is third from

the left, back row. Clyde Combs is third from the right, back row. [Photo: Clyde Combs]

The proposed schedule that would have sent Ron 35 to the Pacific theater was changed while they were in Miami. With the coming allied invasion of Normandy [Operation Overlord], the squadron was told to return to New York where their boats would be loaded onboard cargo ships to be taken to the British Isles and the European theater of operations. The PT boat crews were able to take in the sights while waiting for their ship. Clyde recalled seeing the “Rockettes” at Radio City Music Hall. He also recalled having breakfast with his sister, Marjorie, the morning before they left.

According to Clyde’s diary, four of their boats were loaded aboard a barge that took them to the SS Santiago, a T-2 tanker on May 21, 1944. The tanker carried a full load of 100 octane gasoline. That was less of a concern at that time because the U-boat threat had been greatly reduced. The Santiago joined a convoy of many ships for their voyage to England. After 10 days, they arrived and anchored at Gare Loch in the Firth of Clyde. They were unloaded from the tanker on June 1 and waited for the remainder of Ron 35 boats before heading to the PT boat base at Portland Bill, just south of Weymouth on the English Channel.

PT 515 prepared for their part in the invasion. The Navy component of D-Day was called Operation Neptune, and consisted of an armada of more than 750 ships, 3,500 landing craft and thousands of troops. As they left the English Channel in the early, pre-dawn hours of June 6, Clyde Combs recalled, “I could hear the steady drone of aircraft overhead. As it became brighter, I could see the sky filled with transport planes…many of them towing gliders.”

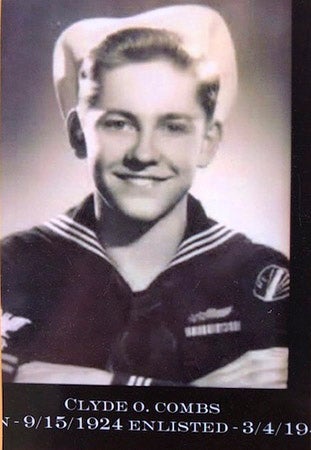

Clyde Combs, Quartermaster First Class, U.S. Navy WW II. Combs and Foreman were crew-mates on PT 515. [Photo: Clyde Combs]

The PT boats often left the line on special missions. On one of these mission, PT 515 picked up the floating body of a dead sailor. The sailor had been aboard the destroyer USS Corry [DD 463], which was sunk when it hit a mine, killing 22 men. The practice was to recommit the body to the sea in a proper burial-at-sea ceremony. Combs recalled, “Ironically, our skipper put Max Foreman, Seaman 1/c of our crew, in charge of the burial. His father was the owner of Foreman Funeral Home in Andalusia, Alabama.”

PT 515 remained on the Mason Line with occasional trips to their primary port at Portsmouth, a trip of about 80 miles across the channel. After the beachhead had been established and the troops had moved inland, the PT boats were given offensive duties in addition to their defensive roles. In late July, the port of Cherbourg had been taken and the PT boats began operating from there.

Clyde Combs recalled two incidents that involved PT 515. The first incident happened near the Channel Islands on September 1, 1944. Their boat was sent from Cherbourg to the north coast of France to the small town of Lezardrieux. Their mission was to determine if the German shore batteries there were still active. They arrived without being fired upon by the Germans and were warmly welcomed by the French citizens. After bartering some Spam and cigarettes for fresh eggs and wine, they left for Cherbourg.

PT 515’s skipper chose to take a shortcut back to base which put them in range of the German batteries on the Channel Islands. They were traveling with the throttle wide open in the pitch-black night, but were soon heard by the Germans. Their big 15 foot “rooster tail” was picked up by the German search lights and they came under fire. Fortunately, they escaped unharmed and made it back to Cherbourg. Another boat, PT 509, was not quite so lucky. They were traveling at night near the Jersey Island [one of the Channel Islands] when they accidentally rammed a German minesweeper in a heavy fog. Only one crewman from PT 509 survived.

Another mission given to the PT boats was to interdict German boats that attempted to escape the port of Le Harvre at night. The German boats were desperate to make it north to German-held ports in Belgium or the Netherlands. On one such mission, PT 515 picked up a target on radar and fired two torpedoes. They immediately laid down a smokescreen and sped away. Despite the smokescreen, they came under fire by German “E-Boats” [German motor torpedo boats that they called Schnellboots, or S-boats]. Combs described the green tracers of the German 20 mm cannons, coming at them as they sped away, “The skipper told me to go to the stern to tell our Torpedoman, ‘Red’ McCloskey to turn on the smoke generator…I headed back to the cockpit after passing along the skipper’s order…After seeing the green tracers of the German shells passing overhead, I decided to hit the deck…the seas were very rough and we didn’t have handrails to protect us from falling overboard…I hit the deck directly over our fuel tanks below deck that were carrying about 3,000 gallons of 100 octane gasoline…I couldn’t have picked a worse place.”

As they were making their escape, one of the German shells hit PT 515 in the bow, just above the waterline. The shell passed right through the ¾ inch laminated mahogany, leaving a large hole but didn’t detonate. Combs recalled, “We radioed our base in Portland, England, about 80 miles away and told them to have a floating drydock ready. We headed back, wide open with our bow well above the water. We made it and nobody on our boat was injured. We never knew the results of the torpedo attack for sure, but we believed we sank one German trawler.”

PT boats underway at flank speed during WW II. Photo belonged to Dr. Max Foreman. [Photo: Donlin Foreman]

After leaving the Navy, Max Foreman returned to Auburn and pursued a degree in veterinary medicine. He graduated at the top of his class and earned his Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree in 1950. As a side note, Max was a member of the same social fraternity at Auburn as the author, the Alpha Iota Chapter of Pi Kappa Phi. Max is mentioned in the fraternity newsletter published in a 1950 edition. The paper referred to Max as “the little professor,” and noted that he was very active in the fraternity and had been on the Deans List numerous times. It also mentioned his WW II service in the Navy and that he had been elected to attend the National Pi Kappa Phi convention. It listed his hobbies as “talking, girls and pretty bird dogs.”

Max Maloy Foreman married Mary Douglass Fundaburk on June 7, 1950. They would have two sons, Donlin Maloy Foreman and Ronlin Douglass Foreman, born July 22, 1952. They also had a daughter, Michelle Cottle Foreman, born November 29, 1954. After graduation, the Foremans moved to Paducah, Kentucky, where Max interned. After that, they moved to Baldwin County, Alabama, where he established the Baldwin Animal Clinic in Foley. It became one of the largest small/large animal practices in the southeastern United States. Dr. Max Foreman retired in the 1980s and was elected to the Baldwin County Commission on two occasions.

After his retirement, Dr. Foreman worked extensively in Bolivia as a veterinary missionary. He taught and educated Bolivian farmers on the health and maintenance of herd animals.

Dr. Max Maloy Foreman died March 21, 2005. Funeral services were held at Mack Funeral Home in Robertsdale, Alabama, on March 24. The funeral was followed by graveside services and burial at Andalusia Memorial Cemetery in Andalusia, Alabama. Dr. Foreman was survived by sons, Donlin Maloy [Jacque] Foreman and Ronlin Douglass [Lydia] Foreman. He was also survived by his daughter, Michelle Foreman [Gene] Leech; his sister, Sara Foreman [Forrest] Hobson; seven grandchildren and nephews, Norman and Jeff Hobson.

John Vick

The author thanks Mr. Clyde Combs for his encouragement and the use of his wartime diary. He also thanks Mr. Norman Hobson for his help in writing about his uncle.

Special note: An article about Mr. Clyde Combs will follow in next week’s paper.

[Sources: Wikipedia; The Mobile Press-Register March 23, 2005 edition; The Andalusia Star June 3, 1948].