Cullen R. Hugghins, Ensign, U.S. Merchant Marine, KIA, WWII

Published 4:00 pm Friday, May 27, 2022

- Ensign Cullen R. Hugghins, U.S. Merchant Marine, Third Assistant Engineer, SS Sam Houston, 1942. [Photo: The Hugghins family]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

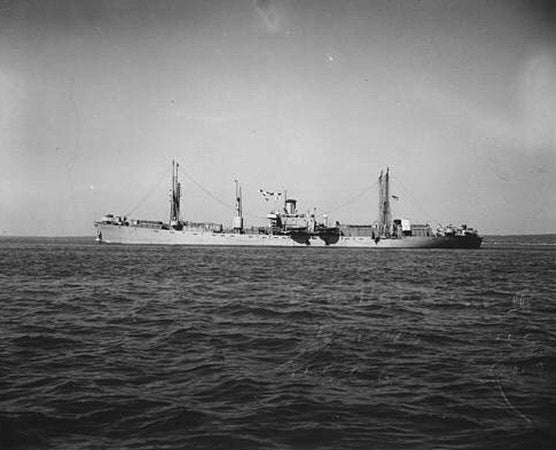

Deep beneath the emerald-blue waters of the Caribbean Sea, just north of the U.S. Virgin Islands, lies the rusting hulk of the U.S. merchant ship, SS Sam Houston. On June 28, 1942, a single torpedo from the German submarine, U-203, struck the Sam Houston. Three men were killed instantly; Third Assistant Engineer Cullen R. Hugghins, Fireman Hamm M. Hall and Oiler Clyde A. Dunning. The ship remained afloat briefly, but in a matter of minutes, it had taken on so much water that her Captain, Robert Perry ordered abandon ship. Three life boats were lowered carrying 43 men and the Sam Houston was left adrift with barely two feet of the ship above the water-line.

Some 20 minutes after the initial attack, Kapitanleutnant Rolf Mutzelburg surfaced his U-boat and finished off the merchant ship with his deck gun. Captain Perry was then brought aboard the U-boat and questioned. He would later recall that the Germans not only knew his name but the name of his ship and its destination. Just six months after Hitler had declared war on the United States, the Germans had spies in place who knew our secrets.

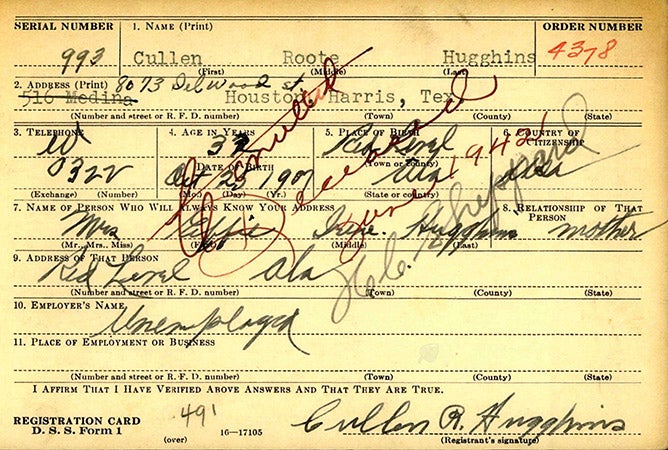

Among the three men killed in the initial torpedo attack on the SS Sam Houston was Cullen Root Hugghins, a native of the Cohassett community, located in Conecuh County, just across the county line from Covington County Alabama. Cullen was born October 25, 1907, to Henry Terry and Effie Barrow Hugghins. He was one of 8 siblings. He graduated Red Level High School around 1925 and moved to Houston, Texas. Cullen was 32 years old when he registered for the draft on October 16, 1940. His residence was listed as Houston, Harris County, Texas. He was unmarried and listed his mother, Effie Hugghins, who lived in Red Level, Alabama, as next-of-kin.

Cullen Hugghins joined the Merchant Marines and trained to be an engineer. We do not have the list of ships on which he served but he had been commissioned an Ensign by the War Department and had worked his way up to Third Assistant Engineer [officer] when he was assigned to the SS Sam Houston for her maiden voyage.

U.S. Merchant ship, SS Sam Houston on her maiden [and last] voyage from Houston, Texas to Capetown, South Africa, via Mobile, Alabama, June 1942. [Photo: armed.guard.com]

On July 2, 1942, Cullen Hugghins’ mother received the following telegram:

MRS. EFFIE IRENE HUGGHINS

RED LEVEL, ALABAMA

THE NAVY DEPARTMENT DEEPLY REGRETS TO INFORM YOU THAT YOUR SON CULLEN ROOT HUGGHINS WAS KILLED AT SEA FOLLOWING ACTION IN THE PERFORMANCE OF HIS DUTY IN THE SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY. THE COAST GUARD EXTENDS TO YOU ITS DEEPEST SYMPATHY IN YOUR GREAT LOSS. TO PREVENT POSSIBLE AID TO OUR ENEMIES PLEASE DO NOT DIVULGE THE NAME OF HIS SHIP.

VICE ADMIRAL R. R. WAIRCHER

COMMANDING COAST GUARD

One can only imagine the pain and anguish of the Hugghins family, especially for the parents. Terry and Effie Hugghins had sent three sons to war but only Cullen was killed. Some of that pain is reflected in a letter from Effie to her daughter, Willie Mae, dated August 11, 1942. The family had just received pictures of Cullen in full dress uniform [One is shown with this article]. The letter was shared by Jo Ann Walton Parham, daughter of Willie Mae and niece of Cullen Hugghins. Excerpts from the letter follow:

“Dear Willie Mae,

Well, we have the pictures at last…..I think they are the very best I have ever seen. It’s just exactly like him. I could sit and look at that picture all day….And to think he’s sleeping in the bottom of the sea is just about to get the best of me, and I can’t help it as hard as I try to turn it off. This tragedy and millions like it caused by one man, that demon Hitler. O Lord, how long will this last?”

Back on June 28, the ordeal of the 43 survivors in the lifeboats had just begun. A diary was kept by one of the survivors, Third-Class Gunners Mate Louis R. Padula. He passed away in 1993 but in 2014, his son, Louis J. Padula, released a copy of the handwritten diary to the website that honors the memory of the crew of the SS Sam Houston.

Padula had just been released from sick bay where he had been for a week when the torpedo struck. Quoting from his June 28 entry, “There was a dull thud and the ship lay over on its side a little bit. It knocked me over. I got up right away and went to wake up a shipmate who was in sick bay with me….we went on the gun deck but we couldn’t see anything . The ship was on fire and the smoke was choking us…Being as we couldn’t fire the guns if the sub came up, the Captain told us to abandon ship. There were a few fellows burned and a few who were in the engine room. We went in the engine room but it was full of water and we could not help them at all.”

After the crew had abandoned ship and got in the lifeboats, Padula took stock of the situation, “There were five men burned real bad and two with minor burns….There were 14 in our lifeboat and only three of us able to do anything….The sub that had torpedoed us came to the top about 30 yards away.…My heart was in my mouth….the first fellow out of the sub pointed a machine gun at us. He waved his hand and we waved back.”

The ship’s cook had been blown overboard and was between the sub and the burning ship. One of the lifeboats went over and picked him up and cleared the area between ships. The sub captain then proceeded to sink the Houston with his deck gun. After that, the sub came alongside one of the lifeboats and tied up. Padula recalled, “They could speak pretty good English. The Captain asked if anybody had any broken bones and offered to send a doctor aboard….We told him there were a few who were burned but he could do nothing for them.”

The men in the other lifeboats had not been injured and were already out of sight by the time Padula’s boat set sail. He recalled later, “A couple of hours after we got going, one of the burned fellows died. We wrapped him in a blanket and tied him up, figuring we could keep him as long as possible and that we would be able to see land soon.”

On July 1, Padula and his fellow crewmen awoke to the beautiful sight of mountains about 40 miles distant. Again Padula recalled, “What a sight! Getting to wonder how many of us would be left when and if we reached land. We reached there in the afternoon. We spotted a patrol plane and the mate ordered me to fire a couple of flares. The plane saw them and flew toward us.

Several of the men got out and swam ashore carrying ropes. They pulled the boat as the others rowed and they eventually made it to the beach. They overturned the boat and placed the injured men out of the sun. By then, the seaplane had returned and landed nearby. After the two injured men were placed onboard the plane, it taxied out to open water and began its takeoff.

Padula again gave his first person account, “Just as he got off the water, a large wave seemed to reach up and touch the plane, just enough to make him crash….We all took off and ran that way, but when we got to the spot, the pilot had both men out and on the beach….Another plane finally came out piloted by a major. In the meantime, one of the two fellows passed away. I guess the crash finished him. We got the last one in the plane and the Major took off.” The whole ordeal had lasted about 10-12 hours.

Draft card of Cullen Hugghins, signed in Houston, Texas, where he worked at the time. Note, written in red across the front: “Cancelled, Deceased, June 1942.” [Photo: ancestry.com]

After the war, one of the survivors from the Sam Houston came by to visit Cullen Hugghins’ family. There is a memorial concrete marker honoring Cullen Hugghins at the Long Branch Cemetery, Cohassett, Conecuh County, Alabama.

John Vick

Postscript: The U-203 met the same fate as so many of Germany’s submarines on April 25, 1943, when she was sunk by British forces. However, Rolf Mutzelburg was no longer in command. He had died on September 22, 1942, when he dove into the water from the conning tower for a swim. A swell picked up the nose of the submarine, causing him to strike his head on the casing.

He died from the accident and was buried at sea.

[Sources: Maritime Quest, “Daily Event for June 28, 2008”; uboat.net; the diary of Louis R. Padula, Gunners Mate Third Class, courtesy of his son, Louis J. Padula; thanks to Jo Ann Walton Parham, Willie Mae’s daughter, for sharing her mother’s letter about Cullen and special thanks to Bill Hugghins, nephew of Cullen Hugghins, who has written extensively about his uncle and shared his information with the author]