Abner Gillis Jones, Sergeant, U.S. Army, Korean War The Accidental Cook

Published 1:00 pm Friday, April 28, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Some historians have referred to the Korean war as “the forgotten war.” Don’t tell that to 93- year-old Gillis Jones. He still remembers his time in Korea, such as the time when he was on the receiving end of a shelling attack. He had returned to his regiment’s base camp and been recruited as a cook. Things had been quiet for some time, but one day, right after Christmas 1951, things suddenly changed. He recalled, “Shells from the N. Korean and Chinese armies began falling in our cooking area. We were scrambling for cover, trying to find any spot that offered protection. The shells were flying over like a covey of quail. Some shells knocked big holes in our ovens. One new recruit broke and ran out from the tent. He was hit by shrapnel and suffered a severe abdominal wound. The medics rushed over to him and placed some kind of mesh over the wound. He was evacuated and taken to Japan. I heard later that he recovered.”

Abner Gillis Jones was born June 22, 1929, in Melrose, Conecuh County, Alabama. His parents were Jesse Leonard and Lula Belle Massey Jones. Gillis was the youngest of three children. He attended Evergreen schools and graduated from Evergreen High School in 1948. For a short time, he worked at Vanity Fair Mills in Monroeville, Alabama. He enjoyed playing for the company’s baseball and basketball teams.

Gillis was drafted in 1950 and sent to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, for basic training. He deployed from Seattle, Washington, aboard the USS General H.W. Butner [APA-113], in April 1951. He was part of the Howe Company [Heavy Weapons], 5th RCT [Regimental Combat Team], 24th Infantry Division. The 5 RCT’s weapons included [in addition to the M-1 rifle], a 75-mm recoilless rifle, a .30-cal. water-cooled machine gun and mortars.

The ship landed in Tokyo before proceeding to Korea. Gillis had two pair of boots when he left Tokyo but the Army took away one pair. Near the port of Inchon, the RCT personnel disembarked upon LCVPs [small landing craft] and dropped the men off in chest-deep water. After wading ashore, they were loaded aboard a train and were taken out into the field for night-training. The train carried them most of the way but they had to march the last 19 miles to the training area.

The training lasted about two weeks, then the men were taken by truck to the front-line area. The fighting at the front-lines was at a stalemate. The terrain was a rocky, mountainous area with the N. Koreans and Chinese on one mountain and the Allied troops, across a valley, on another mountain. The location was north of the 38th parallel in an area called the Iron Triangle.

Gillis recalled, “We replaced the 19th Regiment which had nearly been wiped out. The weather was cool and we set about digging foxholes which wasn’t easy in the rocky soil. There were two men per foxhole and we set up our .30-cal machine gun on the perimeter.

“We would provide overhead fire when a probe was sent towards the enemy. Mortars and heavy artillery also accompanied the attack. At night, the enemy would come down to the base of the mountain where we had a barbed wire barrier. They also had a plane fly over every night which we named ‘Bed-check Charlie.’

“Around Christmas, the N. Koreans set up large speakers and began playing Christmas music.

We didn’t like that so someone shot up their speakers. At night, they would sneak down to the barbed wire barrier and hang paper messages. One that I recall said, ‘Mr. Moneybags is in Miami this Christmas, where are you? In Korea.’”

Gillis had also taken part in the probing attacks. He recalled, “We couldn’t see them at night but we could hear them talking. We didn’t do any firing. After that Christmas, my one pair of boots came apart and I was sent back to the regiment’s base camp for a new pair.”

Gillis recalled, “I was waiting in the kitchen area for my boots when the Mess Sergeant mentioned that one of the cooks was rotating back home and that they didn’t have a replacement. He asked me if I could cook and I said ‘yes.’ That began my career as a cook. I cooked in the kitchen there from January through April.”

The weather was something Jones remembered, “We slept in a tent on air mattresses. One night it rained so much that I woke up floating out of the tent… The winters were really cold. The river near our camp was frozen solid and I saw our tanks driving on them… Even the coffee would freeze on the lips of the cup.

“We made coffee in 25-gallon pots. We cooked hot food and took it to the front-lines by jeep…One night when I was taking food up to the front lines, I forgot the password which changed nightly. I was so scared I’d be shot that I turned around and went back to get the password.”

The shelling action on the cooking area [mentioned in paragraph one] occurred right after Christmas 1951. Gillis recalled, “We were preparing to serve a meal to a platoon that had come down to get a shower. Suddenly, the N. Koreans and Chinese started shelling our area and some shells fell right at our tent. We had our own ammunition and shells stored there. Besides the one young recruit who was severely wounded, there was another soldier who was wounded while sitting in a jeep. We had not been hit with such accurate fire before and our command decided to probe the mountain where the fire was coming from. They returned with a female N. Korean soldier who had been directing fire for them with high-powered field glasses. We saw her as they brought her through camp in a jeep.”

Gillis recalled an incident that left him feeling really sad, “There was another soldier in our regiment who had completed his tour and was going to leave the next day. He was asked to take a new recruit up to the front lines. While he was there, an exchange of gunfire took place and he was killed. I’ll always think about that soldier…He was from East Orange, New Jersey, and so close to going home.”

Gillis’ tour ended in May 1952. The 5th RCT was moved to Pusan, loaded onto a boat and sent to Kojedo Island where N. Korean prisoners were housed. Gillis cooked for the prison guards while he was there. He remembered that some of the hard-line POWs killed some of their fellow prisoners. After Gillis left Korea, he heard that an American one-star general had been captured by the prisoners while visiting the prison.

The 5th RCT arrived back at Seattle in late May. From there, Gillis took a train cross country to Camp Rucker, Alabama, where he was discharged. After a short time, he went to work at Andalusia Hide and Junk, a business that had been started by his grandfather, Huey Richard Jones in 1925. He joined his brother, Brown Jones, as a partner in the business in 1955. Gillis continued to work at the business until his retirement in 1995.

Gillis married Laura Ann Murphy in June 1953. They have three daughters, Sharon Jones [Bibb] Oglesby, Kathy Jones [Richard] Jones and Sara Gilan Jones. Gillis and Laura Ann moved into a new home in River Falls, Alabama, in March 1958, where they still reside.

John Vick

The author thanks Gillis Jones, his daughter, Kathy and the family for their help in writing his story.

[Sources: Wikipedia; The President Harry S. Truman Library; “24th Forward – The Pictorial History of the Victory Division in Korea,” published by the 24th Infantry [Victory] Division Association; and “Gillis Jones” article in the Andalusia Star-News, Feb. 2019 by Michele Gerlach].

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT

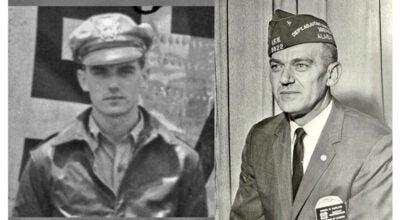

![Gillis Jones in his Army uniform, around 1950-52.

[Photo: Gillis Jones]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-main-web.jpg)

![Gillis Jones[R] with a friend in the cooking area of the Korean camp of the 5th RCT [the same area that was shelled later]. [Photo: Gillis Jones]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-2.jpg)

![Headquarters Company, 5th RCT in Korea] [Photo: 24th Infantry Division Association]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-3.jpg)

![Gillis Jones with a fellow cook with a sign touting their cooking skills. [Photo: Gillis Jones]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-4.jpg)

![The female N. Korean officer who was captured after she was caught spotting for N. Korean artillery that was shelling

the 5th RCT base camp kitchen area where Gillis Jones was working. [Photo: 24th Infantry Division Association]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-5.jpg)

![N. Korean prisoners captured by the 5th RCT. [Photo: 24th Infantry Division Association]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-6.jpg)

![Propaganda leaflet left on a barbed wire fence by the N. Koreans. Gillis remembered

this but this copy was found in the online President Truman Library. [Photo: The Truman Library]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-7.jpg)

![LEFT: Plaque given to Gillis Jones, showing a piece of barbed wire from the DMZ [Demilitarized Zone]. [Photo: Gilan Jones] RIGHT: Back of the plaque given to Gillis Jones. [Photo: Gilan Jones]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-8.jpg)

![Map of the 5th RCT's actions in The Iron Triangle [above the 38th parallel]. [Photo: Wikipedia]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/04/John-Vick-4-28-2023-web-9.jpg)