Memories, photos of WWII sharp

Published 12:07 am Saturday, November 10, 2012

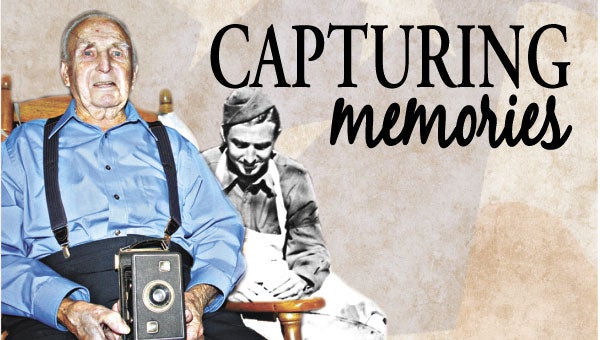

Top: Rufus Grantham holds the Kodak camera he used to capture faces of fellow soldiers before WWII began. Also shown is a younger Grantham.

If a photograph is worth a thousand words, then Andalusia’s Rufus Grantham is a rich man – rich not only because of his ability to document history with a Jiffy Kodak camera, but also for surviving the bloodiest single battle ever fought by American soldiers, the Battle of the Bulge.

Grantham, who is one of Covington County’s 3,000-plus veterans, served as a communications officer. He left Andalusia in September of 1942, transferring from the local National Guard unit, the 1-117th Field Artillery Battalion, to other units before being “dropped” into the 106th Field Artillery Headquarters Battery and occupied Germany.

Grantham wasn’t the only local young man sent to fight in World War II. He spent the time leading up to deployment capturing their training and escapades on film.

Even at 91, he’s still able to call their names like a teacher taking roll, pointing out their faces in a photo-filled scrapbook,…and it’s still hard for him to talk about the event that shaped his life forever.

“When war was declared, most people had to send their cameras home,” he said. “I couldn’t keep mine because I didn’t have enough rank, and I couldn’t keep out of trouble.

“When the draft passed, I was 19, and it was for five years,” Grantham said. “So I said I’ll get my five years over with the National Guard. I’d been in a year (with the 117th) when they said the storm clouds of war were gathering.

“They were right,” he said.

Pearl Harbor happened, launching the U.S. into WWII. Soon, Grantham found himself on the Germanic front.

“It was Dec. 16, 1944, and Germany hit us with what was supposed to be 37 divisions at one time,” he said. “On that morning, my crew was trying to re-establish communications to front lines when we came under fire by a big gun, which we learned later was 14-inch railroad gun.”

And the gunfire didn’t stop, as Grantham experienced his first of many brushes with death while fighting Adolf Hitler’s army. That day, three German armies – more than a quarter-million troops – launched the deadliest and most desperate battle of WWII. The 106th Division was nearly annihilated, but even in defeat, helped buy time for Brig. Gen. Bruce C. Clarke’s brilliant defense of St. Vith. History shows that as the German armies drove deeper into the Ardennes in an attempt to secure vital bridgeheads west of the River Meuse, the line defining the Allied front took on the appearance of a large protrusion or bulge, the name by which the battle would forever be known.

“On the 17th, we were still trying to re-establish communications to the 333rd Field Artillery when we were going down into a ravine when we broke an axle on the truck,” he said. “We stopped to get it rolling again, and a tank column came down the road, straight for us. That axle kept us from meeting that metal column face-to-face.”

On Dec. 18, Grantham’s journey continued, he said.

“The thing about field artillery communication is you’re taught to see and not be seen,” he said. “That night we saw a battalion of German infantry, and I mean we were about 30 feet ahead of them. Don’t know how we got by without being captured.

“Man, it was so cold,” he said. “The worst thing about cold weather is you get so cold, you lose all reason. You get to where you don’t care. That killed a lot of people. Sometimes you had to slap a man in the jaw to get his blood boiling to warm him up.

“The 18th, it was that cold,” he said. “We came under mortar fire. The shell hit and shrapnel came through the canvas of the truck. I was trying to get my socks on my frozen feet.

“Frank J. Mooney from Detroit was with me,” he said. “He had on that wool cap, pushed back and he peeked out from under it and said, ‘Granthy, them sons-of-bitches is (mad) at me and you. We got to get out of here.’ He jumped out the truck, and I stood up to jump. That’s when the f a photograph is worth a thousand words, then Andalusia’s Rufus Grantham is a rich man – rich not only because of his ability to document history with a Jiffy Kodak camera, but also for surviving the bloodiest single battle ever fought by American soldiers, the Battle of the Bulge.

Grantham, who is one of Covington County’s 3,000-plus veterans, served as a communications officer. He left Andalusia in September of 1942, transferring from the local National Guard unit, the 1-117th Field Artillery Battalion, to other units before being “dropped” into the 106th Field Artillery Headquarters Battery and occupied Germany.

Grantham wasn’t the only local young man sent to fight in World War II. He spent the time leading up to deployment capturing their training and escapades on film.

Even at 91, he’s still able to call their names like a teacher taking roll, pointing out their faces in a photo-filled scrapbook,…and it’s still hard for him to talk about the event that shaped his life forever.

“When war was declared, most people had to send their cameras home,” he said. “I couldn’t keep mine because I didn’t have enough rank, and I couldn’t keep out of trouble.

“When the draft passed, I was 19, and it was for five years,” Grantham said. “So I said I’ll get my five years over with the National Guard. I’d been in a year (with the 117th) when they said the storm clouds of war were gathering.

“They were right,” he said.

Pearl Harbor happened, launching the U.S. into WWII. Soon, Grantham found himself on the Germanic front.

“It was Dec. 16, 1944, and Germany hit us with what was supposed to be 37 divisions at one time,” he said. “On that morning, my crew was trying to re-establish communications to front lines when we came under fire by a big gun, which we learned later was 14-inch railroad gun.”

And the gunfire didn’t stop, as Grantham experienced his first of many brushes with death while fighting Adolf Hitler’s army. That day, three German armies – more than a quarter-million troops – launched the deadliest and most desperate battle of WWII. The 106th Division was nearly annihilated, but even in defeat, helped buy time for Brig. Gen. Bruce C. Clarke’s brilliant defense of St. Vith. History shows that as the German armies drove deeper into the Ardennes in an attempt to secure vital bridgeheads west of the River Meuse, the line defining the Allied front took on the appearance of a large protrusion or bulge, the name by which the battle would forever be known.

“On the 17th, we were still trying to re-establish communications to the 333rd Field Artillery when we were going down into a ravine when we broke an axle on the truck,” he said. “We stopped to get it rolling again, and a tank column came down the road, straight for us. That axle kept us from meeting that metal column face-to-face.”

On Dec. 18, Grantham’s journey continued, he said.

“The thing about field artillery communication is you’re taught to see and not be seen,” he said. “That night we saw a battalion of German infantry, and I mean we were about 30 feet ahead of them. Don’t know how we got by without being captured.

“Man, it was so cold,” he said. “The worst thing about cold weather is you get so cold, you lose all reason. You get to where you don’t care. That killed a lot of people. Sometimes you had to slap a man in the jaw to get his blood boiling to warm him up.

“The 18th, it was that cold,” he said. “We came under mortar fire. The shell hit and shrapnel came through the canvas of the truck. I was trying to get my socks on my frozen feet.

“Frank J. Mooney from Detroit was with me,” he said. “He had on that wool cap, pushed back and he peeked out from under it and said, ‘Granthy, them sons-of-bitches is pissed off at me and you. We got to get out of here.’ He jumped out the truck, and I stood up to jump. That’s when the shell hit and blew me out of the truck.”

And he continued to fight, Grantham said. His description of the final day of the battle was short and difficult to talk about to this day.

“We had to shoot our way out,” he said. “From then on, it’s hard to describe. We just had to stop them the best way we could until it was over.”

Grantham eventually served six years, five months and 11 days with the National Guard. After his discharge, he worked in the electrical construction field and retired in 1981.

Eyes squinting, looking to the past, Grantham said, “I remember lot of it like it was yesterday. I served with some good men; I lost some good men. I soldiered with people who didn’t like the military, but I told them we had a job to do. ‘Let’s do it, get it over with and go home,’ I said. That’s still true today.”

shell hit and blew me out of the truck.”

And he continued to fight, Grantham said. His description of the final day of the battle was short and difficult to talk about to this day.

“We had to shoot our way out,” he said. “From then on, it’s hard to describe. We just had to stop them the best way we could until it was over.”

Grantham eventually served six years, five months and 11 days with the National Guard. After his discharge, he worked in the electrical construction field and retired in 1981.

Eyes squinting, looking to the past, Grantham said, “I remember lot of it like it was yesterday. I served with some good men; I lost some good men. I soldiered with people who didn’t like the military, but I told them we had a job to do. ‘Let’s do it, get it over with and go home,’ I said. That’s still true today.”