Powell: County’s legal history includes big cases, good attorneys

Published 1:01 am Friday, September 30, 2016

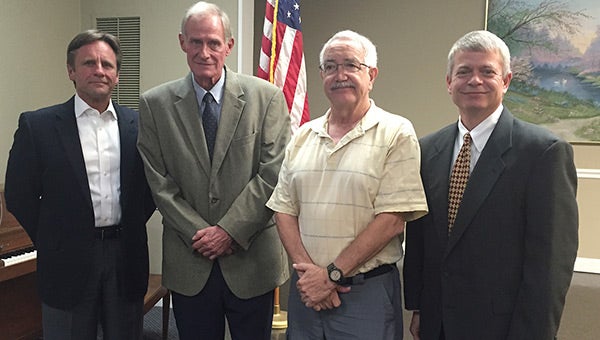

Four the Covington County’s living current and former circuit judges were in attendance at the Covington Historical Society’s meeting Thursday night. Shown from left are Judge Lex Short, former judges Ab Powell and Jerry Stokes; and Judge Ben Bowden.

Covington County’s court system has enjoyed a good professional reputation for more than a century, Ab Powell told members of the Covington Historical Society.

Powell, a mostly-retired attorney, is the third of four generations of Powell lawyers, and began watching cases in court as an East Three Notch Elementary student in the 1950s.

The county has had a strong bar association since the late 1890s, he said.

He recalled his early days in the courtroom when juries were made up of white, male landowners. One of the first times women served as jurors, was in 1955, when Judge Bowen Simmons of Opp hand-selected a jury.

“He had a real custody case,” Powell recalled. “He knew what it was going to be like. He had the idea to empanel an advisory jury, including six women and six pastors. They would hear the evidence, go back and deliberate it, come back and rather than entering verdict on evidence, tell Judge Simmons their recommended verdict.”

Powell’s mother, the late Jean Powell, was among the six women who served. It is believed it was the first time women ever served on the jury in Alabama.

“It wasn’t long after that before we had women on all of the juries in Alabama,” he said, adding that those first Covington County jurors are memorialized in the mural adjacent to the Post Office in Andalusia.

“Times were changing,” he said. “It wasn’t long before we had women on the jury, African Americans on the jury, and anyone else who was qualified as a citizen.”

“The jury system is where democracy really is,” he said. “You get your story, your facts, your case, up there in front of 12 persons qualified to serve. They’ll make a pretty good decision every time. They don’t get it every time. It’s not perfect. I’ve lost cases still haven’t understood how, and I’ve won a couple, when I wasn’t sure how we got to that effect. But it usually works out, and it’s the best system ever devised.”

Capital punishment

Powell said a case his father had when he was 9 years old shaped his feelings about capital punishment.

“I’ve never had capital punishment off of my mind since that time,” he said.

Desmond Miles, who was a native of southeast Georgia, was charged with the death of a soldier in Covington County after the two had been on a drinking binge.

“My dad did not defend him,” Powell said. “He was sentenced to death in 1952. They meant business back then.

“The week before Desmond’s execution, his family came to our house, and employed my father to try to see if he could get a pardon from the governor’s office.

“Gordon Persons was the governor. Daddy didn’t really know him. He went to (Desmond’s) hometown, got affadavits and found witnesses, about the tragic poverty he’d grown up in and the lack of any kind of reasonable advantage. He had no chance. Ever.

“The night he committed the offense, both of them were intoxicated to the point they could barely stand. One thing led to another, and Desmond pulled a gun and shot and killed the other man.”

Powell said his father, Abner Powell Jr., did the best he could in the court system and the governor’s office.

“They weren’t about to reprieve anybody,” he recalled.

“At 11:45 on the night of Desmond’s execution, 10 members of his family showed up on our front steps. I promise I will never forget that scene. Daddy tried to call the governor, and the attorney general at home. He talked to the attorney general, who said, ‘Abner, there’s nothing I could do.’

“At 12:01 a.m., with 10 members of his family on our front steps, he was executed.”

Twice in his time on the bench in the 1970s, the former judge said, he sentenced men to death.

“ I didn’t believe in capital punishment then, and I don’t believe in it now,” he said. “But I was sworn to uphold the law. The jury found the facts of the case, that the men should be convicted, and they should die.”

“Fortunately, neither of the men was executed,” he said. “It didn’t surprise me, and I really didn’t think they would be executed when I sentenced them. There was a flaw in Alabama’s capital offense statute at the time. Didn’t expect them to be executed, and I’m glad they weren’t.”

City courts

Some of his best stories, he said, are from municipal court. As a young attorney, he manned a law office in Opp, and also served as the city’s municipal judge.

At the time, he said, people who drove Buicks or Cadillacs generally traded with J.M. Jackson in Opp. Some who knew he travelled there almost daily would have him drop off their vehicles for repair.

Such was the case the day he got stopped on the way to work driving Eland Anthony’s baby blue Cadillac.

“I was tooling along at about the old Opp Micholas Mills – at that curve,” he said. “They had the speed limit dropped drastically there, and quickly. So I’m tooling in 55 or 60 miles an hour and I see the blue lights go on. I pulled over beside of the road, and I remember the two officers who came up. They said, ‘Oh, Judge, we didn’t know it was you.’ ”

Powell said local police had only just begun to use radar to patrol traffic.

“I asked them what they clocked me doing, and told them to write me a ticket,” he said. “They didn’t want to do it. But what they didn’t know was this was the day of city court in Opp. For about three or four days, I had listened to about 20 people come in my office raising sand (about tickets).

“We showed up in court that night, and I looked around. There were 25 or 30 men out there, banded together. They were mad as hell and it was obvious.

“I asked them to call the first case, and Smitty said, ‘City of Opp vs. Judge Ab Powell.’

“I said, ‘Mr. Powell, how do you plead?’

“Then I walked around to the other side of the bench and said, ‘Judge, they clocked me. I plead guilty.

“Then I sentenced myself to a $15 fine, plus $1.25 court costs. I just happened to have the correct change in my pocket, so I stepped back down and paid it to the clerk and got my receipt.”

He called a brief recess, he said. About 15 minutes later, he said, he and other court officials returned to the courtroom, where everyone who had been there to challenge a ticket had paid his fine and gone home.

Big civil case

Covington County’s court system gained national attention again in the 1970s over a civil case he filed on behalf of 98 farming entities. Local farmers had had a good year, but a grain embargo pushed prices down. Farmers sold what they had to sell to pay their notes at the bank, he said, and stored the rest. Unbeknownst to them, the general manager of Covington Grain traded futures on those soybeans and the farmers lost more than $1 million.

The farmers had three firms refuse the case before the Powell and Sikes firm took it.

The beans had been stored in silos that said ‘New York Terminal Warehouse Inc.” Powell was able to prove that the international company owned the bins, and had keys to the bins, and that the farmers therefore believed they were doing business with them.

Based on a point in a law that basically says, “If you hold a man out as your employee, he can become your employee,” he said. “That’s what happened. The rest is history.”

The farmers were bonded with warehouse receipts that was basically “chicken feed,” he said. But their loss was more than $1 million.

“We went to court, and got a judgment in that amount,” he said. “This was big. They were watching all over the U.S. because New York Terminal was an international company.”

The case was appealed, but the farmers prevailed, and the company eventually paid about $1.5 million to the local farmers.

“That was by far the most important civil court tired in Covington County,” he said. “It changed the way people did business.”

Best local attorneys

When Powell took questions, current Circuit Judge Ben Bowden asked who was the best trial lawyer in front of a jury in Powell’s 50-year career.

“It’d be hard to say just one,” he said. “I’d put Garth Lindsey (of Elba) up against anyone. He worked at Dorsey Trailer coming up. Then one morning he got up, stretched, and went to law school. He was scary good. He knew some law. He knew enough to get in front of that jury. And when he did, you wanted to cover your head, because he could talk the talk and walk the walk and get them to do what he wanted them to do.

“Harold Albritton was not what I would say was a street person. He was very much an intellectual. He was Eagle Scout. He was all-American, and still us. I had the utmost respect for him. I never won a case against Harold Albritton. Never. We settled some cases, but when we went to trial he out-worked you, out-prepared you, or whatever. He was a wonderful lawyer, and is highly regarded and respected.”