Program to include mystery of WWI soldier’s death

Published 2:00 pm Friday, August 4, 2023

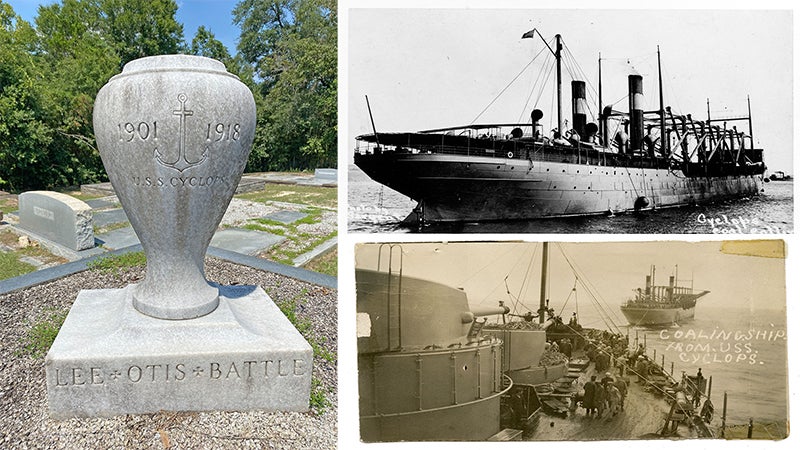

- LEFT: The Battle family placed this memorial to their son in the family plot in Magnolia Cemetery. Battle’s story will be among those featured in ReAct Theatre and Arts’ walking tour of the historic cemetery, ‘Tales from the Tomb,’ on Sat., Oct. 7. (PHOTO PROVIDED) TOP RIGHT: USS Cyclops, circa 1913 The USS Cyclops, circa 1913. (PHOTO: U. S. NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND) BOTTOM RIGHT: The USS Cyclops, in the background, conducting an experimental coaling at sea with the USS South Carolina off the coast of Virginia in April 1914. (PHOTO: U. S. NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The cause of death of one of the first Alabamians to fall in service during World War I remains a mystery, more than 100 years after his ship disappeared.

Born in 1901, Lee Otis Battle was still a teenager when America entered WWI in April of 1917.

The local newspaper, then The Andalusia Star, carried reports of America’s looming involvement.

In what appears to be a special, two-page edition of the newspaper published on Saturday, April 7, 1917, one day after President Woodrow Wilson signed a congressional resolution declaring war, the local headline was “Wilson Signs War Act; Naval Forces Mobilized.”

“By proclamation the president … called upon all citizens to manifest their loyalty and assured Germans in this country that they would not be molested as long as they behaved themselves.”

In an opinion piece, newspaper owner and editor Oscar M. Dugger wrote that the president’s call to duty was not to be taken lightly.

“The days and months ahead of us are to be filled with history making events; of sacrifices which will try men’s souls. In Germany we have an adversary, both powerful and resourceful. She has soldiers trained and hardened to the task of waging war in its most brutal and inhumane form. She has taken into account the full measure of our nations [st.] resources in men, munitions and money … We are up against an enemy which will require our full strength to overcome.”

Even before the official declaration of war, the local newspaper was reporting upon detailed plans for “raising an army numbering millions if that is necessary.”

One cannot know if it was newspaper accounts that persuaded young Battle to enlist. Private radio stations were not yet widespread, and at the declaration of war, President Wilson ordered all stations to be shut down or taken over by the military. Nonetheless, Lee Otis Battle entered Naval service on August 3, 1917.

He was the son of Dr. and Mrs. H.E. Battle. Dr. Battle, who moved his family to Andalusia circa 1900, was a prominent local physician.

Lee Otis was assigned to duty on the USS Cyclops. The Cyclops was 540 feet long and 65 feet wide, and was designed to carry 12,500 tons of coal. When the United States declared war on Germany and its allies, support ships like this one fell under the command of the Navy.

According to the U.S. Naval Institute, the Cyclops sailed from her home port in Norfolk, Va., to Rio de Janeiro with 9,960 tons of coal. She was to return with 11,000 tons of manganese ore, which is used in steel production.

She arrived in Rio de Janeiro 19 days after leaving Norfolk, and remained in port for two weeks unloading and loading cargo. On Feb. 15, 1918, the Cyclops departed Rio for Bahia, Brazil, its only scheduled stop before Baltimore, Maryland. The ship left Brazil on February 22, and was expected to arrive in Maryland on March 13.

Records show the Cyclops made an unplanned stop in Barbados on March 3. After this stop, it was never seen again.

There has been much speculation about the fate of the Cyclops and the 309 crew members who were aboard. Decades after she went missing, Conrad A. Nervig, a former officer who had transferred off the ship in Rio, wrote an article for the U.S. Naval Institute about the problematic ship and her crew. Nervig described the commanding officer, Lt. Commander George W. Worley, as an “indifferent seaman and a poor, overly cautious navigator” who was “generally disliked by both his officers and men.”

Nervig theorized that the Cyclops was split down the middle and quickly sank because the manganese was improperly stored, likely because the only officer on board with experience storing manganese ore was the executive officer, “who was placed under arrest and confined to his room due to a ‘trivial disagreement’ with the captain.”

Nervig explained that the stress at sea could break the ship in two, and that the spaces would quickly fill with water as the ship went vertical, perhaps too quickly for lifeboats to be deployed.

Nervig’s theory about the fate of the Cyclops is one of many. Others include that the ship was lost in the Bermuda Triangle; that the manganese exploded; and that the ship was sunk by a German U-boat. While there is no way to debunk most of the theories, post-war records indicate there were no U-boats in the area at the time.

Word of the missing ship had not yet reached Andalusia, Alabama when Dr. Battle received a heart-breaking telegram. On Tuesday, April 16, 1918, just eight months after Lee Otis Battle joined the Navy, The Andalusia Star reprinted a telegram received by Dr. Battle on Sunday, April 14:

“The Navy Collier Cyclops on which your son, Lee Otis Battle, seaman, second class, U.S.N was a member of the crew is overdue at an Atlantic Port since March thirteenth. She was last reported at one of the West Indian Islands March fourth and no information received from her since that date. Her disappearance cannot be logically accounted for in any way as no bad weather conditions or activities of enemy raiders have been reported in the vicinity of her route. Search for her is being continued by radio and by vessels. Any definite information received you will be at once advised. Address all inquiries to the Bureau of Navigation.”

The newspaper reported that the shock of the telegram was a “crushing blow both to Dr. and to Mrs. Battle, the latter having been in a state of collapse ever since the news came.”

Mr. Dugger wrote that the telegram brought the horror of war home to Andalusia.

“We think of Otis as the bright, happy and companionable boy – a favorite among his associates. We hope that news may yet come that he and all who are board are still safe. But if what we fear shall prove to be true and it proves to be that Andalusia’s first victim was our own jolly Lee Otis, we can feel assured that since we know he met duty like a true American we also know that he met death, if death has come, like a hero.”

Lee Otis Battle also was survived by a brother, Sumpter Elton Battle, and a sister, Evelyn (later Findley).

A month after the telegram was delivered, the newspaper announced that photographs of Lee Otis Battle and Dick Brighton of Florala, two of the three fallen Covington County war heroes, would be shown at the Royal Theatre.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, officially declared the ship lost at sea on June 1, 1918. Battle was one of 12 sailors aboard who called Alabama home, including Bascomb Newton Branson of Whistler; Earl LeBaron Carroll, Oak Grove; Thomas Jackson McKinley, Evergreen; George Mason McNeal, Birmingham; John Freeman Mitchell, Pratt City; William Thomas Wise, Glenmore; and Hamilton Thomas Beggs, Birmingham.

Dr. Battle died rather suddenly of heart failure in 1923 at age 55, but Lee Otis’s mother, Mrs. Jessie Battle, remained active in the community for many years. In 1931, she was invited as a Gold Star Mother to travel to the battlefields of France as a guest of the government.

The Battle-Malcomb VFW Post 3454 was named for Lee Otis Battle and for Lt. James Malcomb, who died at the battle of Chateau Thierey in France. The post was organized in 1936, and had a building on Crescent Street.

SN Battle has a memorial tombstone in the Battle family plot of the historic Magnolia Cemetery behind the Covington County Courthouse, and his will be among the stories shared on Oct. 7 (time TBD) when ReAct Theatre and Arts presents “Tales of the Tomb,” a walking tour of the cemetery narrated by characters who rest in peace there. Auditions will be at 6 p.m. on August 21 in the Church Street Cultural Arts Centre.

Michele Gerlach

Sources: Andalusia Star archives; U.S. Naval Institute website; Alabama Veterans Memorial Foundation; and the archives of the Three Notch Museum.

Michele Gerlach serves on the boards of both Covington Veterans Foundation and ReAct Theatre and Arts. Anyone with additional information about Battle or a photograph is asked to contact her at michele.gerlach@cityofandalusia.com.