PFC Oliver C. Clark, Jr., U.S. Army Part 1: Task Force Smith and The Battle of Osan

Published 1:00 pm Friday, September 8, 2023

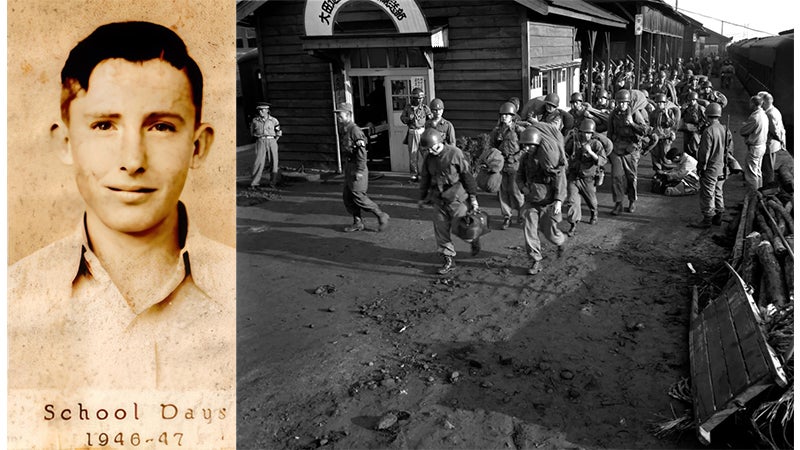

- LEFT: Oliver C. Clark, Jr. [Straughn School Picture] RIGHT: Elements of Task Force Smith entering Tajeon, Republic of Korea on July 2, 1950. [U.S. Army Photo]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Robert Evers, Covington Veterans Foundation

On July 5, 1950, the first ground engagement between the armed forces of the United States and North Korea took place near the small village of Osan, Republic of Korea. A small unit called “Task Force Smith,” consisting of 540 men, faced the advance of 5,000 combat-hardened North Korean troops supported by 36 Russian-made tanks. Private First Class O. C. Clark of Straughn, a rifleman with Company C, 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, fought in this battle. Sadly, he would also become one of the first American casualties of the Korean War.

Oliver Columbus Clark, Jr., born in 1929, was the son of Oliver Clark, Sr. and Mary Elizabeth Wright. The Clarks lived and farmed on Bracewell Road in the Straughn Community. Before enlisting in the U.S. Army and being sent to Japan, he attended Straughn School. He was also known by his nickname, “Buddy.”

On June 25, 1950, the North Korean People’s Army invaded its southern neighbor to unify the country under communist control. This aggression shocked the free world and prompted the newly formed United Nations to come to the aid of South Korea. President Harry Truman granted the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur, the authority to deploy American combat troops to confront the attackers. The nearest units available to be sent to Korea were from the U.S. occupation forces in Japan.

During the years since the end of World War II, the U.S. had allowed its conventional forces to degrade as it shifted emphasis to its nuclear deterrence arsenal. The United States occupation forces were under-trained and equipped with worn WWII weaponry. Most had grown accustomed to the peaceful life of an occupation army. Only about 25% of the unit has seen any combat action in World War II.

Loading the troops and equipment of a large fighting force onto ships for deployment to Korea would require several days. Therefore, it was decided to send a small unit ahead to delay the communist advance until the entire 24th Infantry Division could be deployed from Japan. Its primary purpose was to signal the U.S. resolve and warn the communists that its aggression would be met with force.

Two under-strength companies from the 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army’s 24th Division, were flown from Itsuki, Japan, to Pusan on C-54 transports. A small detachment of engineers and communication specialists supported the infantry. Also attached was an element of the 52d Artillery Battalion consisting of six 105mm light howitzers. This unit was dubbed Task Force Smith after its commander, Lt. Col. Charles B. Smith, a respected veteran of WWII. General William Dean, Commander of the 24th Infantry Division, ordered Smith to move his forces as far north as possible and set up a defensive position to block the advancing North Korean troops.

The deployment of U.S. combat troops to Korea was guised under the term “police action. ” Many early arriving soldiers thought they would only be there a few days and that the North Koreans would rethink their actions at the first site of American troops. Sadly, this would not be the case. The North Korean army was battle-hardened, well-trained, and populated with veterans who had fought with Mao Tse-Tung during the Chinese Civil War.

Arriving in Korea, the rifleman carried only 120 rounds of ammunition and two days of rations. They were equipped with a few outdated bazookas and only a few anti-armor munitions for their recoilless rifles and artillery pieces. One officer observing the unit move out remarked that “they looked like a bunch of Boy Scouts.”

In drizzling rain on the night of July 4, a few miles north of the village of Osan, the task force set up on a small series of hills overlooking the roadway. They dug in the best they could and waited for the attacking Koreans. At 8 a.m. the following day, an advance column of 8 T-34s advanced toward the Americans. The U.S. soldiers opened fire with artillery, recoilless rockets, and bazookas and damaged two tanks. The other tanks ignored the Americans and pushed down the road past them. Soon, another enemy column of tanks and infantry stretching six miles appeared and began an enveloping assault on the American positions.

The Americans were able to hold until early afternoon. Still, the overwhelming number of attackers and dwindling ammunition forced them to begin their withdrawal to the south, which soon turned into a complete rout. Unit cohesion quickly dissolved as the men retreated away from the withering fire of the North Koreans. Those wounded and unable to walk had to be left behind. Of the approximately 540 soldiers in the task force, less than 200 could be accounted for the next morning. Over the next several days, stragglers made their way back to the lines of the newly arrived elements of The U.S. 24th Infantry Division.

According to the Department of Defense, Pvt. Clark was wounded and captured by the North Koreans. He would then endure the infamous “Tiger Death March” toward the North Korean prison camps on the Yalu River.

The Battle of Osan resulted in 60 U.S. killed, with 21 individuals wounded and 82 taken prisoner. Among those captured, 32 died in captivity, 40% of Task Force Smith’s overall strength. North Korean casualties were approximately 42 dead and 85 wounded, with four tanks destroyed or immobilized. Task Force Smith delayed the North Korean advance by seven hours, allowing U.S. units further south to set up the next delaying action. The U.S. Army was pushed steadily southward in the coming days until they could eventually form and hold the “Pusan Perimeter.”

Soon, the unofficial mantra of “no more Task Force Smiths” became well known in the U.S. military to emphasize the importance of combat preparedness.

Note: The author’s knowledge about O.C. Clark, Jr. is derived from his military involvement in the Battle of Osan and the U.S. Department of Defense archives. No known local surviving relatives have been identified at the time of this writing. If you have information on PFC Clark or other veterans of the Korean War, please contact the author at covvets@gmail.com.