Guard unit activated to help protect marchers, campers

Published 12:06 am Saturday, March 7, 2015

There are many things Walter Moore remembers from 50 years ago.

Like how oblivious he and his friends were to what was happening with the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama when, as a member of the Andalusia unit of the Alabama National Guard, they were among those federalized by the president to provide protection.

Like being issued a rifle, but no bullets.

But in the days he and his friends were in service as federal troops, it became more and more clear to him: Nobody knew what was going to happen.

Nobody.

It was 50 years ago this weekend that civil rights activists first attempted to march from Selma toward Montgomery in a peaceful demonstration. The first attempt became known as Bloody Sunday, when Alabama state troopers, some on horseback, and Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark and his deputies used billy clubs and tear gas to drive back marchers. Sixteen people were hospitalized and at least 50 others injured. National coverage of the event galvanized the country

It was the marchers’ third attempt that was eventually successful. By this time, U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson had ordered state troopers not to stop the marchers, who were under the protection of Alabama National Guard troops federalized by President Lyndon B. Johnson. President Johnson also sent 1,000 military policemen and 2,000 Army troops to escort the marchers from Selma.

Moore was an on-again, off-again building construction student at Auburn, but he was off that semester, having just returned from basic training and AIT.

“We were staying in an old national guard armory in Montgomery,’ he recalled. “Real quick, we got caught up on what was going on. Our mission was to guard the marchers.”

The Andalusia unit was part of an artillery battalion. Its members knew nothing about crowd control.

“We were issued our weapons with no bullets,” he said. “Then, and now, that made no sense to me. I guess we were supposed to look so imposing, nobody would bother us.

“We were butchers and postmen and carpenters, regular old truck drivers and guys who knew nothing about trying to control a crowd,” he said. “We were good at artillery.”

At the armory in Montgomery, they learned rudimentary crowd control. Then, they were sent out to protect the marchers who were camping between Selma and Montgomery.

“We were told to form a complete circle around the campsite,” he said. The men, standing in pairs spaced several feet apart, formed a perimeter. They were to let no one in, and no one out. Anyone who did leave had to go all the way around and back to what was deemed the front of the perimeter to get back in.

The camping was primitive, at best. There were no facilities, and based upon the evidence the group left, there was lots of partying going on.

“These were not locals,” he said. “They were not from Alabama. They had long hair and beards, and looked kind of strange to us.”

What happened was remarkable, he said.

“This was a bunch of white, country boys, protecting a bunch of weird-looking people coming from all over the country,” he said of those days. “We followed orders, but we didn’t want to be there.”

There they were, standing guard without bullets, in the dark.

“Nobody knew what to expect,” Moore recalled, adding that at times he and other members of his unit weren’t sure if they were supposed to keep the supporters hemmed up or protect them.

Just as the crowd of marchers was growing along the route to Montgomery, that night the camping crowd was growing, too.

Despite the unknowns, that night passed without incident. The guardsmen went back to Montgomery to practice more crowd control.

“We had guns with no bullets, no gas masks and no tear gas,” he said. “My job that next night was to walk guard around all of our vehicles at the armory. I was walking guard with a rifle with no bullets.”

By comparison, the state of Alabama had pressed everyone from troopers to game wardens into service, and had issued them billy sticks and hard hats.

Moore remembers seeing the stunned looks on officers’ faces as they realized the crowds were growing beyond expectations.

“More and more people came,” he said. “There was still a concern of a counter movement by zealots who were opposed to the movement.

“We didn’t know what to do, or what to expect,” he said. “But we knew we were outnumbered.”

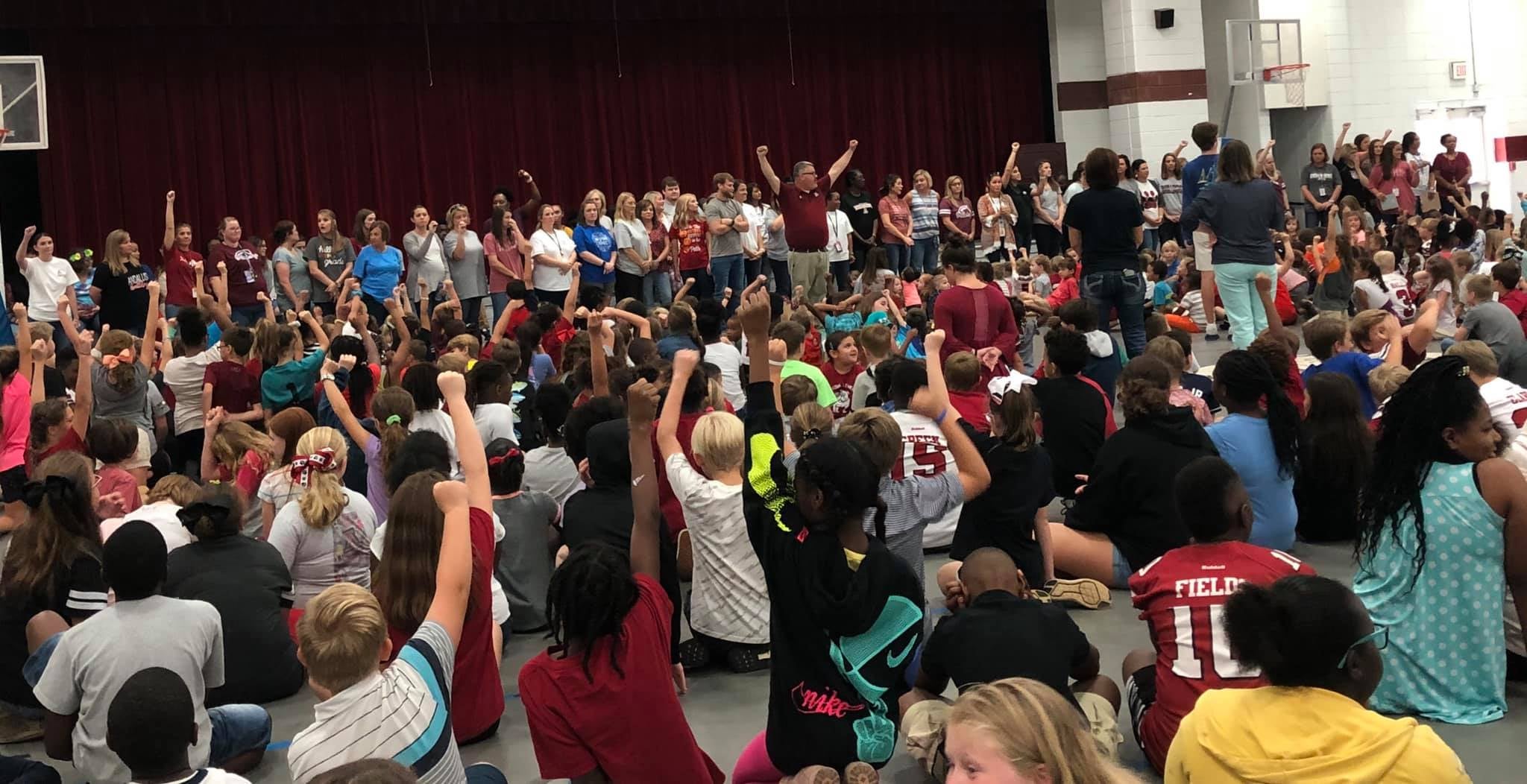

The unit spent a day watching events unfold in Montgomery, and on March 24, 1965, Moore and his friends from Andalusia were among the troops guarding the marchers resting at the City of St. Jude, a Catholic church and school complex on the outskirts of Montgomery, for a “Stars for Freedom” rally. Among the performers that night were Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett, Joan Baez, Sammy Davis Jr., Nina Simone, Frankie Laine and Peter, Paul and Mary.

“Fortunately for me, I was posted very near the stage area,” said Moore, himself a musician. “I had no idea how big the history I was a part of was.

“We were posted there to keep the peace, I guess,” he said. “We weren’t certain how many people were there for the movement, and who might be there against the movement. It’s not like there were two armies who were wearing different uniforms so we could identify them.”

“It was shoulder-to-shoulder crowded,” he said. “I came to believe if a huge crowd of people started moving in a certain direction, how hard it would be to stop them. It wouldn’t have mattered if you had bullets or not.”

In retrospect, Moore said, it’s probably a good thing guardsmen had no bullets that week.

“Our grandfathers and great-grandfathers had taught to be good Democrats because we once were an occupied country … Prejudice is a good word,” he said. “A lot of us have since changed our way of thinking – I know I have.”

Nobody was prepared for what happened, he said of the crowd of marchers whose numbers swelled to 25,000. Almost to a man, he said, no one in his unit supported the cause for which the crowd was marching at the time.

“I can say this for all the guys I went up there with,” he said. “We didn’t want anything bad to happen.”

Looking back, he said, Selma had to happen.

“It was 50 years ago. It’s sad today to see where our minds were then,” he said. “Looking back, I could say I was proud of the way we all behaved. Once the federal government stepped in, it caused some kind of awakening.”

“Nobody in the unit wanted a mixing of the races. That’s sad, but that’s the truth,” he said. “That was prejudice, operating on misinformation, and on lies that were passed down. But we were guarding the very thing we opposed. And we did it.”

And none of them, he said, realized what a big role they were playing in history.