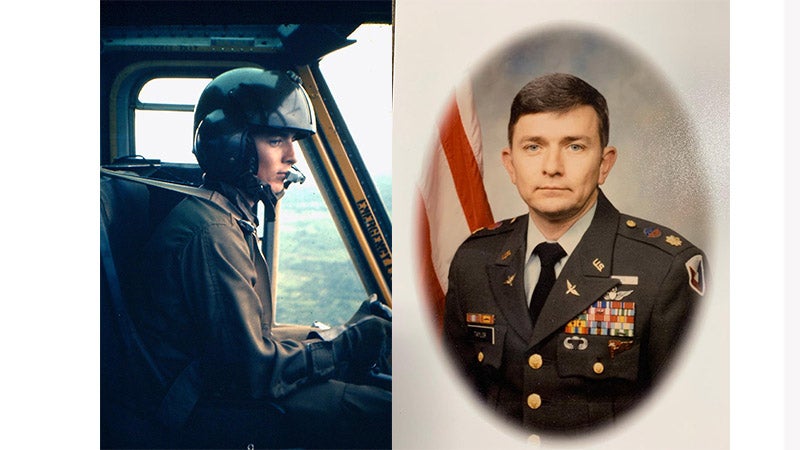

Randy Jack Taylor, Major, U.S. Army, Vietnam Helicopter Pilot, Distinguished Flying Cross

Published 5:01 pm Friday, August 20, 2021

- LEFT: WO1 Randy Jack Taylor at the controls of his UH-1C “Huey” helicopter in Vietnam. RIGHT: Major Randy Jack Taylor at his retirement. He was the recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross. PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE TAYLOR FAMILY

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Air Cavalry concept was created by the Army in 1965 when the 1st Cavalry Division [Airmobile] was organized. This new concept utilized the helicopter to get troops quickly to a combat zone. During the Vietnam war, more than 12,000 helicopters were flown, 5,607 of which were lost to enemy action or accidents. According to the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association, 2,165 pilots and 2,712 crew members gave their lives fighting in Vietnam.

The life of an Army helicopter pilot in Vietnam was dangerous – not just dangerous as in “getting shot at,” but dangerous as in piling into a helicopter in the middle of the night, preparing for an unexpected mission into an unknown area, not in battle-dress but with whatever you could throw on in half-a-minute. Such was life in Vietnam for pilots of the 1st Air Cavalry Division – men like WO1 Randy Jack Taylor.

Randy Jack Taylor at the controls of the Army AC680 fixed wing aircraft [Post Vietnam]

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE TAYLOR FAMILY

Warrant Officer Taylor recalled one such mission that took place in early July 1970.

“Shortly after dark, rockets and mortars started hitting our airfield at Tay Ninh. Operations sent a runner to tell all pilots to get an aircraft and get it gone to prevent it being destroyed. Even though I was still a copilot, I ran to the nearest Huey…in underwear and flip flops, untied the rotor blades, cranked it and took off into the night. Tay Ninh tower would not respond to calls…they had gone to their bunker. There were about 20 all blacked-out [no lights] helicopters flying around …it was a miracle that we didn’t have a mid-air collision. About an hour and a half later, the tower responded and told us the attack was over…we could come back home….This made no sense to a 20-year-old kid….if I were killed on the ground in a rocket/mortar attack or in a mid-air collision…neither made a hell of a lot of sense….I just did what I was told.”

That is just one of the harrowing experiences Taylor recounted.

Randy Jack Taylor was born January 21, 1950 in Douglas, Georgia to Ralph Avery and Geneva Hutcheson. He, his brothers and sisters were reared in Florala, Alabama by James Hubert Taylor and Geneva Hutcheson Taylor. Randy Jack attended Florala schools and graduated from Florala High School in 1968. He worked at a local sewing factory until being drafted in 1969.

WO1 Randy Jack Taylor arrived in Vietnam on June 10, 1970 and was assigned to C Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion, 1st Cavalry Division [Airmobile]. His first combat mission took place 10 days later. He wrote, “We were doing combat assaults from Tay Ninh, Vietnam into Cambodia. We hauled infantry soldiers in and hauled captured weapons out. On the second sortie, we thought we would be hauling out captured weapons but this time we hauled out bodies of dead American soldiers…a hell of a way for a 20 year-old to figure out that you could get killed here…We did the job of medical evacuation aircraft…because none were available. It was routine for our Landing Zone or Pickup Zone to have enemy fire. We normally had gunship and artillery cover to keep the Viet Cong/NVA from killing us. To the Smiling Tigers [D Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Company] I will be eternally grateful for saving my a– more than once….I still remember the fear to this day.”

Later that month, Taylor was the copilot on a night mission flying the Night Hawk aircraft [UH-1H]. The aircraft was equipped with a minigun, Zenon searchlight, .50 caliber machine gun and two M60 machine guns. They received a call for help from the 1st Infantry Division Base at Dau Tieng who were under attack. Taylor wrote, “When we arrived, the crew chief turned on the Zenon searchlight and there were Viet Cong everywhere trying to breach the perimeter of the firebase. We started shooting at anything that was in the wire or outside the wire….and they were shooting at us…a very terrifying thing for a 20-year-old. We ran low on fuel and ammunition and had to land to refuel and rearm. We flew around the perimeter until about 2:00 am when the fog became so dense that we had to land at the firebase. The Viet Cong were no longer a threat because we had killed them all. When we got up the next morning, we saw them loading bodies on 2 ½ ton trucks…there were approximately 100 bodies…We then flew back to Tay Ninh and went to bed… About three hours later, we were awakened and told to get dressed in jungle fatigues and steel helmets. We asked why and were told that a general was coming to give us a medal. We were all awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism. This was awarded for killing, not something that I grew up believing in.”

Taylor and his company flew combat missions into Cambodia through September 1970, yet the official withdrawal date was June 30, 1970.

Taylor wrote, “Why was I still flying there? Wasn’t the Cambodian incursion over? I flew missions up there where I could see the Mekong River just west of Phnom Penh, Cambodia.”

In mid-July 1970, Taylor’s unit was moved 60 miles south to Bien Hoa. “We felt safer because it was nearer to Saigon…not true! The danger was greater there than on remote bases because the Viet Cong/NVA were more concentrated near the cities.”

On one of Taylor’s missions out of Bien Hoa in August, he wrote about another close call. “I was flying copilot with CW1 Steve Adams. We were flying combat assaults into the jungle around 50 miles north of Bien Hoa. I was flying as we attempted to hover down to unload troops through a hole in the jungle created by a bomb…I was hovering at about 2-300 feet when the tail rotor took a hit causing a severe vibration in the aircraft. We were only about 10 feet off the ground when Adams felt the impact and vibration…he rolled off the throttle and we crashed into the bomb crater. All the crew and troops escaped uninjured. We grabbed M-60 machine guns off the aircraft and followed the grunts to another LZ…One of our aircraft picked us up and flew us back to Bien Hoa where we picked up another aircraft and rejoined the fight….One hell of a day and scary as hell. I still dream about crashing into that bomb crater and running through the jungle to escape.”

On September 18, 1970, Taylor wrote, “I was promoted to Aircraft Commander, less than three months from flying my first combat mission. I was 20 years old with less than three months experience as a combat helicopter pilot. What a way to grow up quickly!”

A couple of days later, Taylor went to the Tactical Operations Center [TOC] to check on his next day’s mission. He wrote, “As I was leaving around 8 pm, rockets and mortars started coming in. I was running to the nearest bunker when shrapnel hit me in the chest and right arm…The medics bandaged me up…I was not seriously wounded so I flew the next day. That was the first time I was hurt but there was no calling in sick, no purple heart, no one had time to write it up.”

Late in September, Taylor was assigned to fly a logistics resupply mission in support of Air Cavalry soldiers. Early one morning, they received word that two aircraft from his unit had a mid-air collision.

He wrote, “We immediately proceeded to the site. Both of the aircraft were under the cloud layer, about 200 yards apart and burning. We couldn’t get to them…all eight crew members were dead. Since I was the logistics aircraft, the flight leader called me and said I had to come back and replace one of the downed aircraft. The mission had to go on, no matter that my friends and fellow crewmembers had been killed…I flew 10 flight hours that day – at least 16 duty hours. We didn’t have time to think about our fellow soldiers, we had a job to do.”

In between combat missions, Taylor was called on to take part in the Army’s defoliation project. He described those missions, “We put a 300-gallon tank in the back of the helicopter filled with Agent Orange. We sprayed everywhere except Quan Loi because the Michelin Rubber Plantation was located there. It was improper to kill rubber trees belonging to an ally [France], but it was alright to kill people. The rubber plantation was a safe haven for the Viet Cong/NVA, If you ventured too close they would shoot at you.”

Taylor flew his last mission on May 31, 1971, “I just flew my last combat mission lasting 7.6 flight hours. Not sure if I killed anyone. There certainly was not a going-home party. Just relief to have it over with.”

Certain images were burned into Taylor’s mind, images that would stay with him long after Vietnam. He couldn’t “un-see” the horrific visions that flashed across his memory.

“I hauled numerous dead American soldiers from the jungle and saw the dead eyes of many because they didn’t have the body bags to put them in. Some had their guts hanging out, faces blown off…bleeding and leaking body fluids all over the helicopter floor….I can still see them. After unloading them at the morgue we would hover over the water point and wash out the helicopter…Not a good memory!”

When Taylor returned from Vietnam, he was assigned to the 2nd Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas. While stationed there, he met his future wife, Sylvia Beasley, who was attending Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas. They were married August 27, 1972. They would have two sons, Randy Jack Taylor II and Andrew Scott Taylor.

In 1974, Taylor was assigned to the 210th Aviation Battalion at Fort Clayton, Canal Zone, Panama. While working as the Aviation Safety Officer, he was given the rare opportunity to qualify as a fixed wing pilot. His commanding officer was so impressed with Taylor’s work that he helped him train and qualify in fixed wing aircraft.

Randy J. Taylor earned two college degrees through after hours instruction offered by the Defense Department. He received a B.S. degree from the University of the State of New York in 1978. He later received a M.A. in Business Management from Central Michigan University in 1979.

In 1981, the Army was faced with a shortage of active-duty Captains. Because of his combat record and having earned a baccalaureate degree, Randy J. Taylor was promoted directly from Warrant Officer to Captain [O-3]. After that, he was assigned to NATO [LANDSOUTHEAST] base in Izmir, Turkey for a year. That tour was followed by tours at Fort Benning, Georgia [Infantry Officer Advanced Course]; Fort Polk, Louisiana, 5th Aviation Battalion as Company Commander and Division Aviation Standardization Officer; Missile Command, Redstone Arsenal, Alabama as Missile Procurement and Anti-Tank Missile Test Officer and finally Air Command and Staff College, Maxwell AFB, Alabama as a student. He retired from the Army as a Major in 1991.

In addition to the Distinguished Flying Cross, he had been awarded the Bronze Star, the Air Medal and several other service awards.

After retirement, Randy and the family moved to the Chapel Hill community near Florala, Alabama where they had previously bought property. He operated Flying T & T Trucking for a few years and in 1993, founded T & T Forestry Services with his brother, Walter Taylor. Through the years, Randy had purchased cattle and eventually operated a cattle farm.

Randy Jack Taylor died April 12, 2019 from cancer believed to have been caused by his exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam. He was survived by his wife, Sylvia, two sons, Randy J. Taylor II and Andrew S. Taylor and three grandchildren. Memorial services with full military honors were held at Evans Funeral Home of Florala on April 20. According to his wishes, his remains were cremated and the ashes scattered over the family farm.

— John Vick

[The author wishes to thank Mrs. Sylvia Taylor and her son, Andrew Taylor for their help in writing this tribute to Major Randy Jack Taylor]

[Sources: Wikipedia, Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association]