Charles E. Turner, Lieutenant, U.S. Naval Aviator, Vietnam TWA Captain

Published 2:30 pm Friday, November 11, 2022

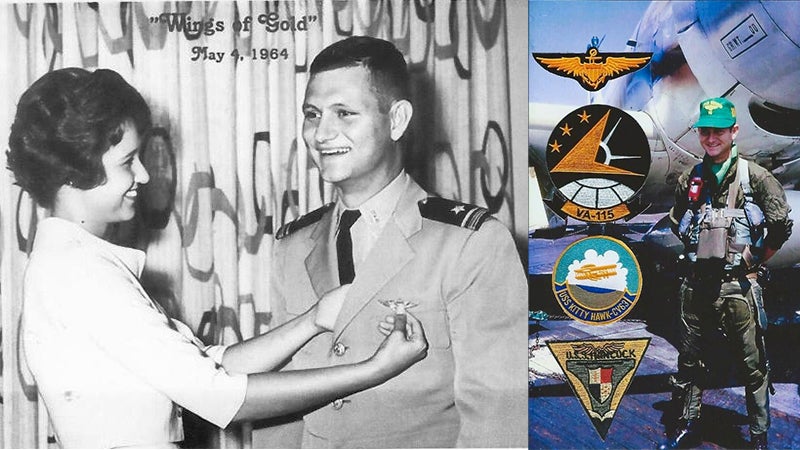

- LEFT: Ltjg. Charles E. Turner has his Naval Aviator Wings pinned on by his wife Diane. [Photo: Charles Turner] RIGHT: Lt. Charles E. Turner in flight suit, standing beside his AD5 Navy Attack aircraft. [Photo: Charles Turner]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The young Navy pilot was over the city of Vinh, North Vietnam, preparing to drop his bombs on the railroad marshalling yards below. He recalled, “I rolled in leisurely, put the “pipper” [visual gunsight marker] on the railroad tracks and released my bombs. Flak was heavy but I wasn’t expecting to see the “telephone pole” headed my way. My “Spad,” [a slang term for the AD5, a Navy bomber] had no early warning for SAMS [surface to air missiles]. The only warning was given on the guard frequency by an Air Force EC 121 [early warning aircraft], and on that day, my guard frequency was down.”

He continued, “The only reason I survived was I saw it coming and managed to complete an evasive maneuver. It was either proximity- fused or sight-detonated and all I remember is that I was engulfed in a huge, orange ball of smoke and fire. The turbulence was real bad and the explosion was loud. My wingman said it looked like a direct hit. I was lucky – the only damage I received was shrapnel through the wings. The underside of the Spad had ¾ inch, armor plating, so the cockpit was spared. That armor plating saved me on several other occasions.”

Charles Edward Turner was born July 16, 1940, in Opp, Covington County, Alabama. His parents were Charles W. and Gertha. O. [Hudson] Turner. Charles attended Opp schools until his family moved to Andalusia in 1955. He and the author became friends and both graduated from Andalusia High School in 1958. They were both recipients of Naval ROTC scholarships to Alabama Polytechnic Institute [became Auburn University in 1960].

Both Charles and the author were members of Pi Kappa Phi social fraternity. The author graduated in August 1962 while Charles earned his BS in Electrical Engineering in December of that year. He was commissioned an Ensign in the Navy on the morning of December 14, graduated that afternoon and married Diane Rowell that evening. The Pastor was the Rev. John Jeffers, the former pastor at First Baptist Church in Andalusia. Their honeymoon was the weekend trip from Auburn to Naval Air Station [NAS] Pensacola to begin flight training that Monday.

Navy Attack Squadron 115 [VA-115] aboard the USS Hancock. Lt. Charles Turner is second from the left, front row. Standing on the far right is Turner’s roommate, Lt. Bob Marvin, who was killed during a night launch due to engine failure. [Photo: Charles Turner]

VA-122 was the Replacement Air Group for the Douglas AD5 Skyraider [Navy attack/bomber aircraft]. Charles completed training in the AD5 and was assigned to VA-115 [Nicknamed “The Arabs”] in June 1965 and he joined the squadron as a Lieutenant, Junior Grade [Ltjg]. His first tour in Vietnam began in October 1965. Charles and his squadron were deployed aboard the USS Kitty Hawk [CV-63], which took its place on “Yankee Station” in the Gulf of Tonkin. He completed about 80 combat missions flying the AD5 Skyraider.

Missions varied from flying close air support for ground troops in South Vietnam to flying bombing missions over North Vietnam. The pay load for the AD5 could be two 500 lb. bombs or a single 1,000 lb. bomb or napalm. It could also carry 800 rounds of 20 mm incendiary or hard-nosed bullets.

Charles described the AD5’s missions, “Our missions included night reconnaissance, air to ground attack, flak suppressions, close air support, PT boat patrol and my favorite, support for Search and Rescue [SAR] missions. I was involved with several successful SAR missions over North Vietnam and those were the most satisfying.” Sometimes a pilot would not be aware that he had taken rounds from automatic weapons until the post-flight inspection.

Piloting planes from a Navy aircraft carrier is one of the most dangerous occupations in aviation. Carriers launch planes from a catapult system that can launch an aircraft every 20-30 seconds. When an aircraft is launched, it accelerates to roughly 120 knots in 1-2 seconds. The recovery of an aircraft by catching a wire with its tail-hook is called a “trap.” The cycle of launching and recovering aircraft in all kinds of weather, day and night, is one of the most complex and dangerous missions in the Navy.

Navy flight operations are dangerous even in peacetime. Charles Turner recalled the loss of several crewmates, “My best friend and roommate, Lt. Bob Marvin, was lost on a night launch in bad weather when his engine failed. Another good friend was shot down on a night- bombing mission and a third squadron mate died in a mid-air crash at night over North Vietnam. I lost three other squadron mates to non-combat related aircraft accidents during shore duty between deployments. Out of 22 pilots in the squadron, that was a pretty high percentage.”

Naval aviators perform the duties of the LSO [Landing Signal Officer] on days when they are not flying. There are two LSOs, one who talks to the pilot and one who records the landing event. They stand on the port side of the flight deck, near the stern, and one holds a “pickle switch” that is used to aid pilots in landing. That LSO holds the pickle overhead until he is given a “clear deck” signal [meaning there are no obstructions or other aircraft fouling the deck]. The pilot making an approach for a carrier landing must pick up the OLS [Optical Landing System] located on the port side, just off the flight deck] when he turns for his final approach. The complex OLS consists of a group of Fresnel lights that direct the pilot on an optimal glidepath to an arrested landing on the deck [where a plane’s tail-hook catches one of four arresting cables.Author’s note: The bright light in the center of the OLS is called “the meatball.” As soon as the pilot picks up the meatball, he calls “the ball,” to let the LSO know he has the lights in view. The OLS shows the pilot “where he is” in relationship to the optimal glidepath for a safe landing. The LSO monitors the pilot’s glidepath and helps the pilot with commands such as, “You’re low, add power,”” etc. He can signal a “wave-off” if the plane is outside the correct glidepath. He does this with a button on the pickle switch that causes the OLS to flash red.

Naval aviators are trained to catch the third of four arresting cables [called wires] with the plane’s tail-hook. As soon as the plane’s landing gear hits the flight deck, the pilot pushes the engine throttles to the maximum, so that he can become airborne in the event that he did not catch a wire. Having full engine power allows the pilot fly off the deck and make another approach [referred to as a “bolter”]. Catching the #1 wire is a “no, no,” because it means that the pilot’s approach was too low, near the back ramp of the flight deck. Charles related two events that happened when he was the recording LSO, “We had one senior pilot who caught the #1 wire on several occasions. On this one day, he hit the ramp and was killed. On another day, an F8U pilot came in too low, struck the ramp, wiping out his landing gear. He managed to get airborne and had to come alongside the carrier and eject.” He added, “Night landings on a pitching flight deck were always dangerous, particularly when the pilot was low on fuel. Getting everyone onboard safely was quite a challenge.”

Charles Turner’s combat tour aboard the Kitty Hawk lasted from October 1965 through May 1966. After a six-month turnaround in the States, he deployed for his second combat tour aboard the USS Hancock [CV-19]. That tour lasted six months, and Charles recalled, “We were older and wiser. We no longer looked for targets of opportunity in ‘hot areas.’ Bombing palm trees and killing monkeys no longer seemed that important to us. On my last mission over North Vietnam, I flew wing for a senior commander. I told him I didn’t want to fly overland and get shot at – we did both.” Charles flew about 60 combat missions from the Hancock and was promoted to Lieutenant [O-3]. He had also performed several collateral duties in addition to his combat flights, including Division Officer, Weapons Training Officer, Weapons Officer and Landing Signal Officer.

Captain Charles E. Turner [right] beside his MD-80 after his last flight, ending a 33 year career with TWA. [Photo: Charles Turner]

In January 1968, Charles began training as a flight crew member for TWA. He spent the first few years as a Flight Engineer and instructor at the training facility at Kansas City, Missouri. When he became a First Officer, he flew the Boeing 727 out of Kansas City, then later from St. Louis, Missouri. Charles recalled, “When I upgraded to Captain, I flew the MD-80 out of St. Louis until the last few years of my career. Most of my flights were coast to coast by then.” Charles Turner retired as a Senior Captain in July 2000 at the mandatory age of 60. He had been with TWA for 33 years. His last flight was from Las Vegas [where his plane was given the traditional firetruck wet-down], to St. Louis, where his family boarded for the last leg of the flight to Kansas City where the flight terminated with another firetruck wet-down.

Charles and Diane currently live in Kansas City, Missouri. Their daughter, Stephanie, and husband, Matt, live in Seabrook, Texas, where Matt is employed by NASA. Matt is an engineer and his team is in charge of the development of the module aboard the Orion rocket which is scheduled to launch this month [November 2022]. Charles and Diane also have a son, Stephen, [Angie] who is an over the road driver with UPS who also lives in Kansas City. Charles and Diane also have four grandchildren.

Both Charles and the author have strong feelings about the political nature of the Vietnam War. After returning from Vietnam, Charles said, “I have come to realize the futility of fighting a political War.” Many Americans would agree with this patriotic Vietnam hero who risked his life fighting in a war because he was asked to do so by his country.

John Vick

The author thanks his friend, Charles Turner and his wife, Diane, for sharing his story.