Edward Eugene “Jack” McGowin, Corporal, U.S. Marine Corps, Vietnam War

Published 1:00 pm Friday, June 16, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Jack McGowin wasn’t even supposed to be on the Huey helicopter when it went down from enemy fire. He had to fight the life-threatening injuries from the crash and the Marine Corps at the same time, just to prove that he was there.

Jack McGowin was born October 10, 1945, in Greenville, Alabama. His parents were Mattie Lou de’Orsay and Francis Arnold McGowin. Jack had an older brother, Francis Arnold, Jr. and a younger brother, Robert Allen. At the time, the family lived in Georgiana, Alabama. Jack’s father was in the timber business and the family moved often. Jack attended schools in Caryville and Vernon, Florida, before they moved to Andalusia, Alabama, in 1957. Jack graduated from Andalusia High School in 1964.

In high school, Jack was enrolled in the DO [Diversified Occupation] program, and worked two years for Clyde Duggan in his auto repair shop. After graduation, he enrolled in George C. Wallace Technical School for a couple of years.

Jack McGowin’s life took a big turn in April 1966, when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. After completing basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, he was sent to Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, for advanced training. From there, he was sent to Memphis Naval Air Station, Tennessee, where he studied at the Aviation School from August 1966-February 1967. He was trained in maintaining and repairing aircraft structures.

From March through November 1967, Jack was assigned to VMFA-334 [Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 334], 3rd Marine Air Wing [MAW], at El Toro Marine Air Station, California. In November, he was deployed to Chu Lai Airbase, Vietnam, and assigned to VMFA-115, 1st MAW. Maintenance work was done on the squadron’s F-4 Phantom jets using three crews working eight-hour shifts [Jack worked the night shift]. The squadron kept several aircraft [called hot pad birds] in revetments, near the pilot’s ready-room, 24 hours day. They were able to be deployed on very short notice for ground support and other emergency missions.

After Jack had returned home, he noted that his mother had all three sons deployed to Vietnam for five consecutive Christmases. That may have been a point of pride but it wasn’t easy for the parents.

The Tet Offensive began around January 1, 1968. In Jack’s words, “All hell broke loose!” The base at Chu Lai, like most U.S. bases during that time, was under almost constant attack. Sometimes Jack and some of his fellow Marines would volunteer to fly as door gunners on the Army’s Huey gunships when they were off duty. Jack had done this, six-eight times until a near-fatal flight in late February.

On February 27, Jack volunteered to be a door gunner on a helicopter that was part of a three-ship flight that was to insert two, five-man combat fire teams near Hill 747 [he’s not sure of the hill number]. Since Chu Lai lies on the Tonkin Gulf, the hill was inland, about 20 minutes flying time. The lead ship would fly cover for the other two while they dropped their fire teams at the LZ [landing zone].

Jack’s ship was the second to drop their men at the LZ, and they began circling at about 1,200 feet in order to provide fire support if needed. Suddenly, the fire teams called and said, “Get us out of here!”. Immediately, the other helicopter began a descent to the LZ, closely followed by Jack’s ship.

Jack recalled, “The other ship began taking rounds and pulled up. About that time, I heard our ship’s turbine suddenly screaming out of control. I was the starboard door gunner and I glanced over my shoulder at the co-pilot. I can still remember that altimeter as it began unwinding…five hundred, four hundred, three hundred etc. I braced for impact and was thrown clear, just down the hill from the crash site at the LZ. When I hit the ground, I glanced up and saw the helicopter begin rolling down the hill toward me.

“When the ship rolled over me, the open side door protected me except for my right leg, which was crushed by the door frame. The helicopter rolled a little further and came to a stop. I looked at my left boot which was cocked up beside my head and thought, ‘that’s gonna hurt.’”

By that time, the pilot and co-pilot had gotten out of the crashed ship and made their way back to Jack. They grabbed him under the arms and began dragging him back up the hill to the LZ. The lead helicopter hovered over them as they climbed the hill. Jack said, “They were hovering overhead, not more than 10 feet above us. It looked like I could have grabbed one of the landing skids.”

At the LZ, Jack and the crew were loaded into the helicopter and taken back to Chu Lai. Jack was stabilized at a field hospital and then flown to a larger hospital at Qin Yan where he was evaluated and treated. After a couple of days, Jack was flown to a hospital in the Philippines. He was then flown to a large Army hospital at Kadena Airbase on Okinawa.

From the time Jack was severely injured in the helicopter crash, he had administrative problems explaining why a Marine Aviation Mechanic was flying as a door gunner on an Army helicopter. Since he had volunteered, there had been no official orders explaining why he was aboard that helicopter.

It was standard protocol for a Marine officer to immediately visit the home of an injured or deceased Marine. Jack had called his family from the hospital in Okinawa and had sent a photo of him in a hospital bed. After hearing nothing from the Marine Corps, his mother and father drove to a Marine Reserve Center in Montgomery, Alabama. They met with a Marine Captain and asked if he knew about Jack’s injuries and hospitalization.

The Captain stepped out of the room and returned saying that his records indicated that Jack was still at Chu Lai. Jack’s mother produced the photo of Jack in a hospital bed which prompted the Captain to leave the room again. This time he returned and acknowledged that Jack was indeed injured. To date, the Marine Corps still has not awarded Jack McGowin a Purple Heart.

It is conjecture, but it is likely that Jack’s commanding officer did not want to acknowledge authorizing his men to volunteer to fly on Army helicopters. Since he did not report Jack’s injuries, the Maine Corps did not record the incident.

Jack was treated on Okinawa and placed in what was called “Casual Company,” for those men not able to return to Vietnam. After several weeks, Jack was given emergency leave to visit his father who was dying. After his father’s death, he returned to Okinawa and continued treatment. Some 15 months later, after much rehabilitation, Jack was sent back to the States and assigned to a small Marine Air Reserve Unit located at Dobbins AFB in Marietta, Georgia. Jack continued to have problems with his knee and was sent to the Naval Hospital in Charleston, South Carolina, for further evaluation.

The Medical Evaluation Board at Charleston sent Jack home on Convalescent Leave to complete his enlistment. He received his Honorable Discharge on May 31, 1969.

After his discharge, Jack attended LBW Junior College under the GI Bill. Jack married Brenda Jordan in 1972, the same year he opened McGowin’s Garage. He and Brenda had one daughter, Susan, who was born in 1975. Brenda died in 1983 and Jack became a single parent. Jack had hired several good workers at his garage and he was able to take time off to get Susan to school and back. Jack married Carolyn Huckabaa in 1997. Carolyn had a daughter, Michelle, and two sons, Lenny and Eric. Carolyn died in 2021. Jack currently resides in Red Level, Alabama.

John Vick

The author thanks Jack McGowin for sharing his story. Our country has produced many brave soldiers and Marines like Jack, and we must never forget their sacrifices.

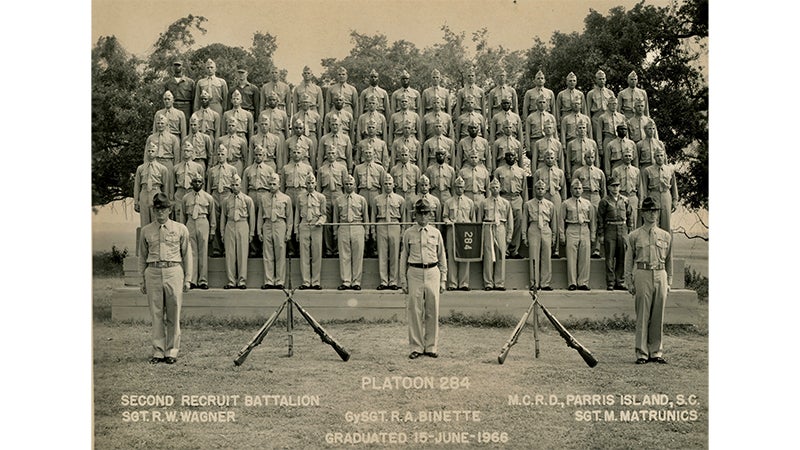

Jack McGowin’s platoon at basic training graduation in June 1966. Jack in in the front row [right] with his hand on the guidon. [Photo: Jack McGowin]

More COLUMN -- FEATURE SPOT

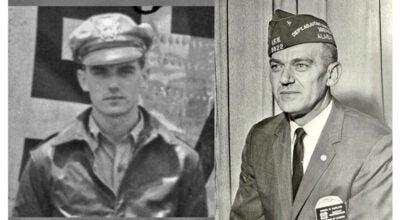

![LEFT: Private Jack McGowin, U. S. Marine Corps after completing basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, in 1966. [Photo: Jack McGowin] RIGHT: Jack McGowin beside an F-4 Phantom fighter of VMFA-334 at El Toro Marine Air Station, California in 1966. [Photo: Jack McGowin]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/06/John-Vick-6-16-2023-main-web.jpg)

![Jack McGowin's platoon at basic training graduation in June 1966. Jack in in the front row [right] with his hand on the guidon. [Photo: Jack McGowin]](https://www.andalusiastarnews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2023/06/John-Vick-6-16-2023-main-web-2.jpg)