Andrew Douglas Franklin, Sr., Tech/Sergeant, U.S. Army Air Corps, WWII Prisoner of War – Part 2

Published 1:00 pm Friday, July 21, 2023

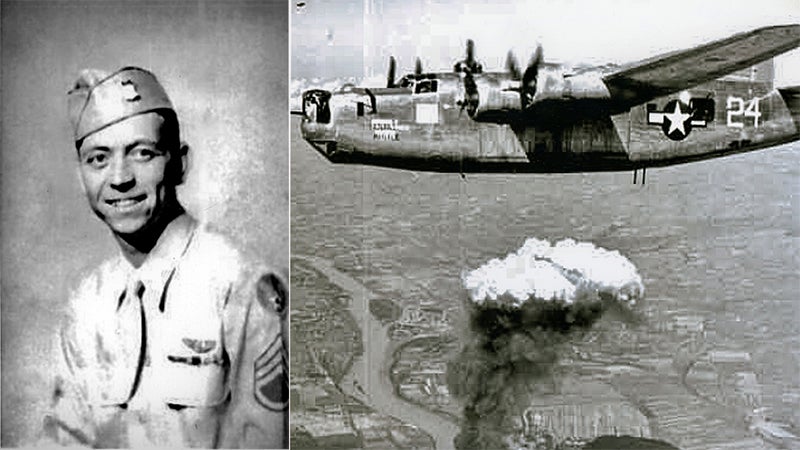

- LEFT: Wartime photo of Sgt. Andrew Douglas Franklin, ball turret gunner, B-24 Liberator bomber, WW II. [Photo: Karen Franklin McGlaun] RIGHT: Photo of Franklin's B-24, "War Eagle" over Ploesti oil works in Rumania. [Photo: Karen Franklin McGlaun]

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As soon as the bomber formation, including Sgt. Douglas Franklin and his crew on the B-24, War Eagle, approached their target at Linz, Austria, they came under heavy attack by swarms of enemy fighters. The sky was thick with flak. The flight of 21 bombers was surrounded, above, below and to the sides, with black puffs of smoke that hid the deadly shrapnel from exploding German anti-aircraft shells.

The target that morning was the Herman Goering Tank Works. The flight of B-24 Liberator bombers was led by Major William Burke of the 766th Squadron who flew the lead plane. His plane was the first to go down.With their leader shot down, the inexperienced pilots of his squadron and those of the 764th squadron, allowed the formation to spread out, instead of packing in close where they could better defend themselves. They were being attacked by 25 twin-engine [ME-110] and 125 single-engine [ME-109] German fighters. Eleven of the 21 U.S. bombers were lost in the raid. A nose-gunner in one of the planes that returned, said that he counted 32 parachutes in the air at one time. Of the 113 officers and men shot down that day, seven officers and nine enlisted men were on their 50th mission including Sgt. Douglas Franklin.

When the fighters attacked Franklin’s plane, it caught fire. The top-turret gunner, Yancey Fulcher [from Geneva, Alabama], and the right-waist gunner, James Hagen, were killed immediately. The tail-gunner, Jose Salas [on his first flight with this crew], was severely wounded. The pilot, 2nd Lt. Richard Freeman, sounded the alarm and announced, “Abandon ship.”

Sgt. Franklin with his crew beside a B-24 Liberator bomber. Franklin is shown, bottom, far left. [Photo: Karen Franklin McGlaun]

Franklin’s parachute opened just before hitting the ground. He landed in a large, plowed field and he could see a tree line in the distance. Pretty soon, he heard the sound of soldiers and dogs. Franklin had heard that the Germans sometimes shot armed airmen so he threw his pistol away and took off for the tree line. As soon as he got there, he found a small gully, crawled in it and pulled limbs and debris over himself. It wasn’t long before he heard a dog close by, then suddenly, the dog’s nose appeared, just inches from his face. Franklin said he was afraid to even breathe, but the dog soon wandered off without so much as a bark.

Franklin had been shot down around 11:30 a.m., and by mid-afternoon, he was tired and thirsty and decided to surrender. He walked into the nearby town of Haag and surrendered to the German soldiers that had been looking for him. Several more of his crew had also been captured. After the men had been interrogated, they were placed on rail cars and taken to Gross Tycho, Pomerania [now Poland]. After they arrived, the prisoners were forced to march and run to Stalag Luft IV, some three miles away.

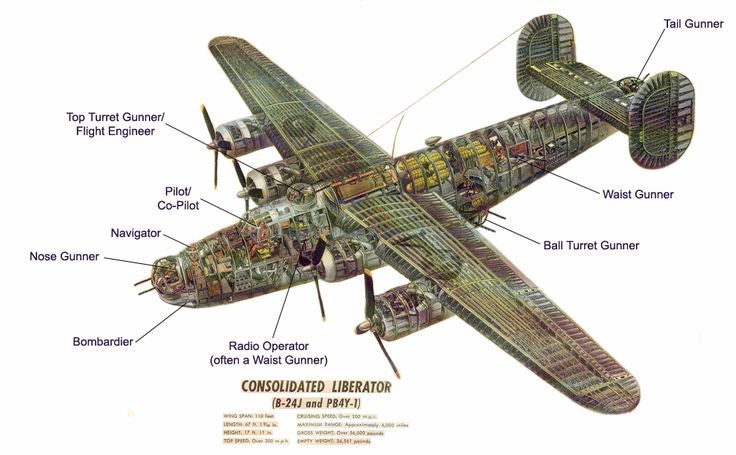

Diagram showing armament on the B-24 Liberator bomber. Note the gun turrets. Sgt. Franklin was the ball turret gunner on the bottom of the aircraft. The aircraft had a range of 2,100 miles when lightly loaded. Range decreased with the heavier loads. [Photo: Encyclopedia Brittanica]

On the way to the prison, the men were beaten if they slowed down or fell out. Several prisoners had been injured when they parachuted and they got the worst of the beatings.

Stalag Luft IV was opened in May 1944, just a couple of months before Franklin’s arrival. The camp quickly developed a bad reputation. In a Red Cross report issued in October 1944, conditions were described as “generally poor,” with “inadequate shower facilities, poor and insufficient food and unfit distribution of Red Cross packages.”

The camp was divided into five compounds, A through E, that were separated by barbed wire. Prisoners were housed in 40 wooden barracks, each containing 200 men. Prisoners in two compounds had triple-tiered bunks while prisoners in the other three slept on the floor. None of the barracks were heated and there were only five small coal-burning stoves in the camp. Guards were ill-tempered and brutal. Franklin remembered one particularly brutal guard who was about six and a half feet tall and weighed about 250 pounds. The prisoners named him “Big Stoop.”

The prisoners were fed twice daily, once in the morning and once more, late in the afternoon. Franklin remembered that his meals were mostly, bread, thin soups such as potato or cabbage and no meat. At one point, Franklin traded his flight jacket and wedding ring to an SS guard for bread. He cut hair for cigarettes. When he entered the camp, Franklin weighed about 144 pounds. When he was released, he weighed less than ninety pounds. He remained in the camp from July 1944 – February 1945, during the coldest winter Europe had seen in more than 25 years. Temperatures averaged close to zero degrees and reached minus 30 degrees at times.

In February 1945, the Germans abandoned many of the prison camps in the east, ahead of the advancing Russian army. The released prisoners were broken up into small groups and marched to the west into Germany. Those prisoners unable to march were put on trains headed into Germany. Franklin remembered the long, difficult march. He said that the Germans marched them in one direction until they neared the Allied lines, then marched them in a different direction until they were close again. Finally, they were boxed in and the Germans just left.

During the march, their only food was scrounged from farms along the way. Franklin said that they sometimes bargained for food and at other times, they just took it. Some of the farmers offered them food, but food was scarce, even for the farmers. Franklin traded his Straughn High School ring to one farmer for bread and syrup.

The prisoners sometimes ate snow for water and at other times, drank water from ditches. Many of them developed dysentery and other disease from contaminated water. At night, they tried to sleep in a barn which offered some protection from the weather.

Franklin recalled that on May 2, he woke up in a small town and realized that the German guards had left during the night and that British soldiers had arrived. The British army did their best to attend to the malnourished prisoners and offer them food. The British told the prisoners to take anything they wanted from the farms in the area. At one abandoned farm house, Franklin came across a beautiful set of dueling pistols on a wall. He wanted to take them but did not have the strength to get them off the wall. Many prisoners became sick from overeating. The liberated prisoners were returned to the American lines on May 6.

After Germany surrendered, most of the American prisoners were transported to Camp Lucky Strike located at St. Valery, France. The camp was part of the Red Horse staging area, located about 45 miles from the port of Le Havre. After Franklin and other prisoners-of-war had been examined and their paper work processed, they were sent home by ship from Le Havre.

Douglas Franklin had been awarded the Air Medal with four Oak Leaf Clusters, The American Campaign Medal [Europe], the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal and the WW II Victory Medal.

When Franklin arrived in New York City in June 1945, he said that his first meal was fried chicken. From there, he was sent to Miami, Florida, by train. After a short stay there, he was sent to a convalescent hospital at Macon, Georgia, and was discharged on November 10, 1945. He came home a few days later and was nearly knocked down by his wife when she ran out to greet him.

Using the GI bill, Douglas Franklin enrolled at Alabama Polytechnic Institute [now Auburn] in 1946 and began studies in Aeronautical Engineering. He left Auburn in 1949 before earning his degree and moved to Opp, Alabama. He taught vocational education to veterans at Blue Springs School for a time and did bookkeeping for several companies including Bryan Oil Company. At various times, Franklin did small engine repair, upholstered furniture and sold insurance.

Franklin loved country music and was a big Hank Williams fan. He played several stringed instruments but was most talented with the guitar, which he held high on his chest. He wrote poems, songs and always kept things around his home lively.

Andrew Douglas Franklin died March 6, 1976 at the age of 53. His funeral was held at Foreman Funeral Home, Andalusia, Alabama, on March 8. He was buried at Pilgrim’s Rest Cemetery in Crenshaw County, Alabama. He was pre-deceased by his mother, Irene Marvin Adams Franklin; a sister Nancy Inez Franklin; two brothers, Horace Vernon Franklin and Donald Lee Franklin; and a son Andrew Douglas Franklin, Jr. He was survived by his father, Dennis Lee Franklin; sisters, Gladys Franklin Dawkins and Ruth Franklin; sons, Allan Butler Franklin, Kenneth Eldred [Gail] Franklin, Terry Kyle Franklin, Timothy Eugene Franklin; Marvin Craig Franklin; daughters Diane Franklin [Steve] Tucker, Sherry Franklin [Biggs] and Karen Franklin [McGlaun]; and numerous grandchildren.

John Vick

The author would like to thank Allan Franklin and Karen Franklin McGlaun for their help in writing their father’s story. May we always remember and honor the memories of The Greatest Generation.

[Sources: Wikipedia; Voces Oral History Center, University of Texas at Austin [Jose M. Salas]; www.461bg.org; www.15thaf.org; Army Air Corps Museum – WW II; American Air Museum in Britain].